Testifying for civil commitment

Help unwilling patients get treatment they need

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

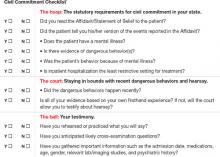

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”