Vitamin deficiencies and mental health: How are they linked?

Identifying and correcting deficiencies can improve brain metabolism and psychopathology

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Patients today often are overfed but undernourished. A growing body of literature links dietary choices to brain health and the risk of psychiatric illness. Vitamin deficiencies can affect psychiatric patients in several ways:

- deficiencies may play a causative role in mental illness and exacerbate symptoms

- psychiatric symptoms can result in poor nutrition

- vitamin insufficiency—defined as subclinical deficiency—may compromise patient recovery.

Additionally, genetic differences may compromise vitamin and essential nutrient pathways.

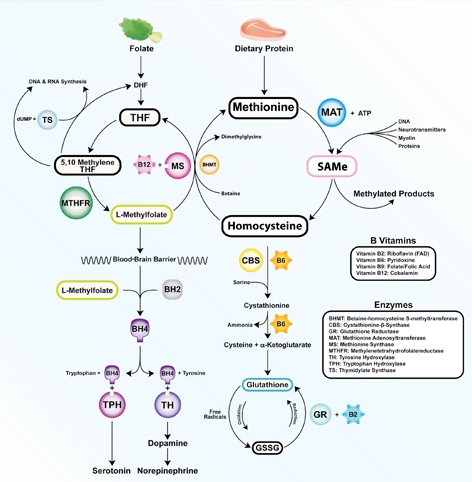

Vitamins are dietary components other than carbohydrates, fats, minerals, and proteins that are necessary for life. B vitamins are required for proper functioning of the methylation cycle, monoamine production, DNA synthesis, and maintenance of phospholipids such as myelin (Figure). Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E play important roles in genetic transcription, antioxidant recycling, and inflammatory regulation in the brain.

Figure: The methylation cycle

Vitamins B2, B6, B9, and B12 directly impact the functioning of the methylation cycle. Deficiencies pertain to brain function, as neurotransmitters, myelin, and active glutathione are dependent on one-carbon metabolism

Illustration: Mala Nimalasuriya with permission from DrewRamseyMD.com

To help clinicians recognize and treat vitamin deficiencies among psychiatric patients, this article reviews the role of the 6 essential water-soluble vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and C; Table 1,1) and 3 fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, and E; Table 2,1) in brain metabolism and psychiatric pathology. Because numerous sources address using supplements to treat vitamin deficiencies, this article emphasizes food sources, which for many patients are adequate to sustain nutrient status.

Table 1

Water-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (thiamine): Glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle | ||||

| Rare; 7% in heart failure patients | 5% total, 12% of older women | Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, memory impairment, confusion, lack of coordination, paralysis | Older adults, malabsorptive conditions, heavy alcohol use. Those with diabetes are at risk because of increased clearance | Pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ. Raw fish, tea, and betel nuts impair absorption |

| B2 (riboflavin): FMN, FAD cofactors in glycolysis and oxidative pathways. B6, folate, and glutathione synthesis | ||||

| 10% to 27% of older adults | <3%; 95% of adolescent girls (measured by EGRAC) | Fatigue, cracked lips, sore throat, bloodshot eyes | Older adults, low intake of animal and dairy products, heavy alcohol use | Dairy, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes |

| B6 (pyridoxal): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 11% to 24% (<5 ng/mL); 38% of heart failure patients | 14% total, 26% of adults | Dermatitis, glossitis, convulsions, migraine, chronic pain, depression | Older adults, women who use oral contraceptives, alcoholism. 33% to 49% of women age >51 have inadequate intake | Bananas, beans, potatoes, navy beans, salmon, steak, and whole grains |

| B9 (folate): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 0.5% total; up to 50% of depressed patients | 16% of adults, 19% of adolescent girls | Loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, heart palpitations, behavioral disorders | Depression, pregnancy and lactation, alcoholism, dialysis, liver disease. Deficiency during pregnancy is linked to neural tube defects | Leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans, and peas |

| B12 (cobalamin): Methylation cycle (cofactor methionine synthase) | ||||

| 10% to 15% of older adults | <3% to 9% | Depression, irritability, anemia, fatigue, shortness of breath, high blood pressure | Vegetarian or vegan diet, achlorhydria, older adults. Deficiency more often due to poor absorption than low consumption | Meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy |

| C (ascorbic acid): Antioxidant | ||||

| 7.1% | 31% | Scurvy, fatigue, anemia, joint pain, petechia. Symptoms develop after 1 to 3 months of no dietary intake | Smokers, infants fed boiled or evaporated milk, limited dietary variation, patients with malabsorption, chronic illnesses | Citrus fruits, tomatoes and tomato juice, and potatoes |

| EGRAC: erythrocyte glutathione reductase activation coefficient; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide; FMN: flavin mononucleotide Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Table 2

Fat-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (retinol): Transcription regulation, vision | ||||

| <5% of U.S. population | 44% | Blindness, decreased immunity, corneal and retinal damage | Pregnant women, individuals with strict dietary restrictions, heavy alcohol use, chronic diarrhea, fat malabsorptive conditions | Beef liver, dairy products. Convertible beta-carotene sources: sweet potatoes, carrots, spinach, butternut squash, greens, broccoli, cantaloupe |

| D (cholecalciferol): Hormone, transcriptional regulation | ||||

| ≥50%, 90% of adults age >50 | 69% | Rickets, osteoporosis, muscle twitching | Breast-fed infants, older adults, limited sun exposure, pigmented skin, fat malabsorption, obesity. Older adults have an impaired ability to make vitamin D from the sun. SPF 15 reduces production by 99% | Fatty fish and fish liver oils, sun-dried mushrooms |

| E (tocopherols and tocotrienols): Antioxidant, PUFA protectant, gene regulation | ||||

| Rare | 93% | Anemia, neuropathy, myopathy, abnormal eye movements, weakness, retinal damage | Malabsorptive conditions, HIV, depression | Sunflower, wheat germ, and safflower oils; meats; fish; dairy; green vegetables |

| HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; SPF: sun protection factor Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Water-soluble vitamins

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is essential for glucose metabolism. Pregnancy, lactation, and fever increase the need for thiamine, and tea, coffee, and shellfish can impair its absorption. Although rare, severe B1 deficiency can lead to beriberi, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ataxia, nystagmus), and Korsakoff’s psychosis (confabulation, lack of insight, retrograde and anterograde amnesia, and apathy). Confusion and disorientation stem from the brain’s inability to oxidize glucose for energy because B1 is a critical cofactor in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Deficiency leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory cytokines, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction.2 Wernicke’s encephalopathy is most frequently encountered in patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetes, or eating disorders, and after bariatric surgery.3 Iatrogenic Wernicke’s encephalopathy may occur when depleted patients receive IV saline with dextrose without receiving thiamine. Top dietary sources of B1 include pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ.