Potentially Inappropriate Use of Intravenous Opioids in Hospitalized Patients

Physicians have the potential to decrease opioid misuse through appropriate prescribing practices. We examined the frequency of potentially inappropriate intravenous (IV) opioid use (where oral use would have been more appropriate) in patients hospitalized at a tertiary medical center. We excluded patients with cancer, patients receiving comfort care, and patients with gastrointestinal dysfunction. On the basis of recent guidance from the Society of Hospital Medicine, we defined IV doses as potentially inappropriate if administered more than 24 hours after an initial IV dose in patients who did not have nil per os status. Of the 200 patients studied, 31% were administered potentially inappropriate IV opioids at least once during their hospitalization, and 33% of all IV doses administered were potentially inappropriate. Given the numerous advantages of oral over IV opioids, this study suggests significant potential for improving prescribing practices to decrease risk of addiction, costs, and complications, ultimately improving the value of care provided.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Recently released guidelines on safe opioid prescribing draw attention to the fact that physicians have the ability to curb the opioid epidemic through better adherence to prescribing guidelines and limiting opioid use when not clinically indicated.1,2 A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine includes 16 recommendations for improving the safety of opioid use in hospitalized patients, one of which is to use the oral route of administration whenever possible, reserving intravenous (IV) administration for patients who cannot take food or medications by mouth, patients suspected of gastrointestinal (GI) malabsorption, or when immediate pain control and/or rapid dose titration is necessary.2 This recommendation was based on an increased risk of side effects, adverse events, and medication errors with IV compared with oral formulations.3-5 Furthermore, the reinforcement from opioids is inversely related to the rate of onset of action, and therefore opioids administered by an IV route may be more likely to lead to addiction.6-8

Choosing oral over IV opioids has several additional advantages. The cost of the IV formulation is more than oral; at our institution, the cost of IV morphine is 2.5-4.6 times greater than oral. Additional costs associated with IV administration include nursing time and equipment. Overall, transitioning patients from IV to oral medications could considerably lower costs of care.9 Ongoing need for an IV line may also lead to avoidable complications, including patient discomfort, infection, and thrombophlebitis. In addition, the recent national shortage of IV opioids has necessitated better stewardship of IV opioids.

Despite this recommendation, our observations suggest that patients often continue receiving IV opioids longer than clinically indicated. The goal of this study was to identify the incidence of potentially inappropriate IV opioid use in hospitalized patients.

METHODS

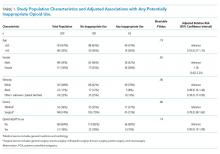

The present study was an observational study seeking to quantify the burden of potentially inappropriate IV opioid use and characteristics predicting potentially inappropriate use in the inpatient setting at a large academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts, using retrospective review of medical records.

Definition of Potentially Inappropriate Use and Study Sample

We identified all hospitalizations during the month of February 2017 with any order for IV opioids using pharmacy charge data and performed chart reviews in this sample until we reached our prespecified study sample of 200 hospitalizations meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria further defined below.

We defined potentially inappropriate use of IV opioids as use of IV opioids for greater than 24 hours in a patient who could receive oral medications (evidenced by receipt of other orally administered medications during the same 24-hour period) and was not mechanically ventilated. This definition is consistent with recommendations in the recently released consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine.2 We selected a time frame of 24 hours because IV pain medications may be indicated for initial immediate pain control and rapid dose titration; however, 24 hours should be sufficient time to determine opioid needs and transition to an oral regimen in patients without contraindications. After an initial IV dose, additional IV doses within 24 hours were considered appropriate, whereas IV doses thereafter were considered potentially inappropriate unless the patient had nil per os status, including medications. All IV opioids administered within 24 hours of a surgery or procedure were considered appropriate. Because it may be appropriate to continue IV opioids beyond 24 hours in patients with an active cancer diagnosis, in patients who have chosen comfort measures only, or in patients with GI dysfunction (including conditions such as small bowel obstruction, colitis, pancreatitis), we excluded these populations from the study sample. Patients admitted to the hospital for less than 24 hours were also excluded from the study, because they would not be at risk for the outcome of potentially inappropriate use. Doses of IV opioids administered for respiratory distress were considered to be appropriate. Given difficulty in identifying the appropriate time to transition from patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) to IV or per os (PO) opioids, days spent receiving opioids by PCA or continuous IV drip were excluded from the analysis.

We used Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-square test (in the setting of a multicategory variable) to calculate bivariable P values. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify independent predictors of receipt of at least one dose of potentially inappropriate IV opioids, using the hospitalization as the unit of analysis.