A Matter of Urgency: Reducing Clinical Text Message Interruptions During Educational Sessions

BACKGROUND: Text messaging is increasingly replacing paging as a tool to reach physicians on medical wards. However, this phenomenon has resulted in high volumes of nonurgent messages that can disrupt the learning climate.

OBJECTIVE: Our objective was to reduce nonurgent educational interruptions to residents on general internal medicine.

DESIGN, SETTING, PARTICIPANTS: This was a quality improvement project conducted at an academic hospital network. Measurements and interventions took place on 8 general internal medicine inpatient teaching teams.

INTERVENTION: Interventions included (1) refining the clinical communication process in collaboration with nursing leadership; (2) disseminating guidelines with posters at nursing stations; (3) introducing a noninterrupting option for message senders; (4) audit and feedback of messages; (5) adding an alert for message senders advising if a message would interrupt educational sessions; and (6) training and support to nurses and residents.

MEASUREMENTS: Interruptions (text messages, phone calls, emails) received by institution-supplied team smartphones were tracked during educational hours using statistical process control charts. A 1-month record of text message content was analyzed for urgency at baseline and following the interventions.

RESULTS: The interruption frequency decreased from a mean of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.88 to 0.97) to 0.59 (95% CI, 0.51 to0.67) messages per team per educational hour from January 2014 to December 2016. The proportion of nonurgent educational interruptions decreased from 223/273 (82%) messages over one month to 123/182 (68%; P < .01).

CONCLUSIONS: Creation of communication guidelines and modification of text message interface with feedback from end-users were associated with a reduction in nonurgent educational interruptions. Continuous audit and feedback may be necessary to minimize nonurgent messages that disrupt educational sessions.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

On general medical wards, effective interprofessional communication is essential for high-quality patient care. Hospitals increasingly adopt secure text-messaging systems for healthcare team members to communicate with physicians in lieu of paging.1-3 Text messages facilitate bidirectional communication4,5 and increase perceived efficiency6-8 and are thus preferred over paging by nurses and trainees. However, this novel technology unintentionally causes high volumes of interruptions.9,10 Compared to paging, sending text messages and calling smartphones are more convenient and encourage communication of issues in real time, regardless of urgency.11 Interrupting messages are often perceived as nonurgent by physicians.6,12 In particular, 73%-93% of pages or messages sent to physicians are found to be nonurgent.13-17

Pages, text messages, or calls not only interrupt day-to-day tasks on the ward6,7,10,11,17,18 but also educational sessions,18-21 which are essential to the clinical teaching unit (CTU). Interruptions reduce learning and retention22 and are disruptive to the medical learning climate.18-20,23

Internal medicine CTUs at our large urban academic hospital network utilize a smartphone-based text messaging tool for interdisciplinary communication. Nonurgent interruptions are frequent during educational seminars, which occur at our institution between 8 AM and 9 AM and 12 PM and 1 PM on weekdays.10,11,19 In a preliminary analysis at one hospital site, an average of three text messages (range 1-11), 2 calls (range 0-8), and 3 emails (range 0-13) interrupted each educational session. Physicians and nurses can disagree on the urgency of messages or calls for the purposes of patient care and workflow.6,11,12,24 Nurses have expressed a desire for guidance regarding what constitutes an urgent clinical communication.6

This project aimed to reduce nonurgent text message interruptions during educational rounds. We hypothesized that improved decision support around clinical prioritization and reminders about educational hours could reduce unnecessary interruptions.

METHODS

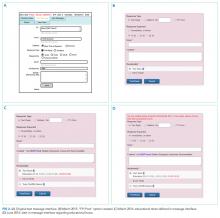

This study was approved by the institution’s Research Ethics Board and conducted across 8 general medical CTU teams at an academic hospital network (Sites 1 and 2). Each CTU team provides 24-hour coverage of approximately 20–28 patients. The most responsible resident from each team carries an institution-provided smartphone, which receives secure texts, phone calls, and emails from nurses, social workers, physiotherapists, speech language pathologists, dieticians, pharmacists, and other physicians. Close collaboration with the platform developer permitted changes to be made to the system when needed. Prior to our interventions, a nurse could send a text message as either an “immediate interrupt” or a “delayed interrupt” message. Messages sent via the “delayed interrupt” option would be added to a queue and would eventually lead to an interrupting message if not replied to after a defined period. Direct phone calls were reserved for especially urgent or emergent communications.

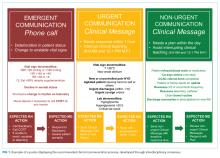

Meetings were held with physicians and nursing managers at Site 1 (August 2014) and Site 2 (January 2015) to establish consensus on the communication process and determine clinical scenarios, regardless of time of day, that warrant a phone call, an “immediate interrupt” text, or a “delayed interrupt” text. In March 2015, resident feedback led to the addition of a third option to the sender interface. This option allowed messages to be sent as “For Your Information (FYI)” only, which would not lead to an interruption. “FYI” messages (for example, to notify that an ambulance had been booked for a patient), were instead placed in an electronic message board that could be viewed by the resident through the application. This change relied upon interdisciplinary trust and a commitment from residents to ensure that “FYI” messages were reviewed regularly.

Statistical process control charts (u charts) assessed the frequency of each type of educational interruption (text, call, or email) per team on a monthly basis. The total educational interruptions per month were divided by the number of educational hours per month to account for variation in educational hours each month (for example, during holidays when educational rounds do not take place). If call logs or email data were unavailable for individual teams or time periods, then the denominator was adjusted to reflect the number of teams and educational hours in the sample for that month.

Two 4-week samples of interrupting text messages received by the 8 teams during educational hours were deidentified, analyzed, and compared in terms of content and urgency. A preintervention sample (November 17 to December 14, 2014) was compared to a postintervention sample (November 14 to December 11, 2016). Messages from the 2014 and 2016 samples were randomized, deidentified for date and time, and analyzed for urgency by 3 independent adjudicators (2 senior residents and 1 staff physician) to avoid biasing the postintervention analysis toward improvement. Messages were classified as “urgent” if the adjudicator felt a response or action was required within 1 hour. Messages not meeting these criteria were classified as “nonurgent” or “indeterminate” if the urgency of the message could not be assessed because it required further context. Fleiss kappa statistic evaluated agreement among adjudicators. Individual urgency designations were compared for each message, and discrepant rankings were addressed through repeated joint assessments. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and comparison against communication guidelines. In addition, messages reporting a “critical lab,” requiring physician notification as per institutional policy, were reclassified as “urgent.” The proportion of “nonurgent” messages sent during educational hours was compared between baseline and post-intervention periods using the Chi-square test.

“FYI” messages sent from November 14 to December 11, 2016 were audited using the same adjudication process to determine if “FYI” designations were appropriate and did not contain urgent patient care communications.