When are Oral Antibiotics a Safe and Effective Choice for Bacterial Bloodstream Infections? An Evidence-Based Narrative Review

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Traditionally, BSIs have been managed with intravenous antimicrobials. However, whether intravenous antimicrobials are necessary for the entirety of the treatment course in BSIs, especially for uncomplicated episodes, is a more controversial matter. Patients that are clinically stable, without signs of shock, or have been stabilized after an initial septic presentation, may be appropriate candidates for treatment of BSIs with oral antimicrobials. There are risks and costs associated with extended courses of intravenous agents, such as the necessity for long-term intravenous catheters, which entail risks for procedural complications, secondary infections, and thrombosis. Oral antimicrobial therapy for bacterial BSIs offers several potential benefits. When selected appropriately, oral antibiotics offer lower cost, fewer side effects, promote antimicrobial stewardship, and are easier for patients. The decision to use oral versus intravenous antibiotics must consider the characteristics of the pathogen, the patient, and the drug. In this narrative review, the authors highlight areas where oral therapy is a safe and effective choice to treat bloodstream infection, and offer guidance and cautions to clinicians managing patients experiencing BSI.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Approximately 600,000 BSI cases occur annually, resulting in 85,000 deaths,1 at a cost exceeding $1 billion.2 Traditionally, BSIs have been managed with intravenous antimicrobials, which rapidly achieve therapeutic blood concentrations, and are viewed as more potent than oral alternatives. Indeed, for acutely ill patients with bacteremia and sepsis, timely intravenous antimicrobials are lifesaving.3

However, whether intravenous antimicrobials are essential for the entire treatment course in BSIs, particularly for uncomplicated episodes, is controversial. Patients that are clinically stable or have been stabilized after an initial septic presentation may be appropriate candidates for treatment with oral antimicrobials. There are costs and risks associated with extended courses of intravenous agents, such as the necessity for long-term intravenous catheters, which entail risks for procedural complications, secondary infections, and thrombosis. A prospective study of 192 peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) episodes reported an overall complication rate of 30.2%, including central line-associated BSIs (CLABSI) or venous thrombosis.4 Other studies also identified high rates of thrombosis5 and PICC-related CLABSI, particularly in patients with malignancy, where sepsis-related complications approach 25%.6 Additionally, appropriate care of indwelling catheters requires significant financial and healthcare resources.

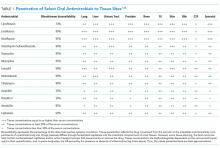

Oral antimicrobial therapy for bacterial BSIs offers several potential benefits. Direct economic and healthcare workforce savings are expected to be significant, and procedural and catheter-related complications would be eliminated.7 Moreover, oral therapy provides antimicrobial stewardship by reducing the use of broad-spectrum intravenous agents.8 Recent infectious disease “Choosing Wisely” initiatives recommend clinicians “prefer oral formulations of highly bioavailable antimicrobials whenever possible”,9 and this approach is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention antibiotic stewardship program.10 However, the expected savings and benefits of oral therapy would be lost should they be less effective and result in treatment failure or relapse of the primary BSI. Pathogen susceptibility, gastrointestinal absorption, oral bioavailability, patient tolerability, and adherence with therapy need to be carefully considered before choosing oral antimicrobials. Thus, oral antimicrobial therapy for BSI should be utilized in carefully selected circumstances.

In this narrative review, we highlight areas where oral therapy is safe and effective in treating bloodstream infections, as well as offer guidance to clinicians managing patients experiencing BSI. Given the lack of robust clinical trials on this subject, the evidence for performing a systematic review was insufficient. Thus, the articles and recommendations cited in this review were selected based on the authors’ experiences to represent the best available evidence.