Improving Quality of Care for Seriously Ill Patients: Opportunities for Hospitalists

As the shift to value-based payment accelerates, hospitals are under increasing pressure to deliver high-quality, efficient services. Palliative care approaches improve quality of life and family well-being, and in doing so, reduce resource utilization and costs. Hospitalists frequently provide palliative care interventions to their patients, including pain and symptom management and engaging in conversations with patients and families about the realities of their illness and treatment plans that align with their priorities. Hospitalists are ideally positioned to identify patients who could most benefit from palliative care approaches and often refer the most complex cases to specialty palliative care teams. Though hospitalists are frequently called upon to provide palliative care, most lack formal training in these skills, which have not typically been included in medical education. Additional training in communication, safe and effective symptom management, and other palliative care knowledge and skills are available in both in-person and online formats.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Palliative care is specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family. In all settings, palliative care has been found to improve patients’ quality of life,1,2 improve family satisfaction and well-being,3 reduce resource utilization and costs,4 and, in some studies, increase the length of life for seriously ill patients.5

Given the frequency with which seriously ill patients are hospitalized, hospitalists are well positioned to identify those who could benefit from palliative care interventions.6 Hospitalists routinely use primary palliative care skills, including pain and symptom management and skilled care planning conversations. For complex cases, such as patients with intractable symptoms or major family conflict, hospitalists may refer to specialist palliative care teams for consultation.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines the key primary palliative care responsibilities for hospitalists as (1) leading discussions on the goals of care and advance care planning with patients and families, (2) screening and treating common physical symptoms, and (3) referring patients to community services to provide support postdischarge.7 According to data in the National Palliative Care Registry,8 48% of all palliative care referrals in 2015 came from hospitalists, which is more than double the percentage of referrals from any other specialty.9

In a recent survey conducted by SHM about serious illness communication, 53% of hospitalists reported concerns about a patient or family’s understanding of their prognosis, and 50% indicated that they do not feel confident managing family conflict.10

IMPROVING VALUE

Context

Patients with multiple serious chronic conditions are often forced to rely on emergency services when crises, such as uncontrolled pain or dyspnea exacerbation, occur after hours, resulting in the revolving-door hospitalizations that typically characterize their care.11 As the prevalence of serious illness rises and the shift to value-based payment accelerates, hospitals are under increasing pressure to deliver efficient and high-quality services that meet the needs of seriously ill patients. The integration of standardized palliative care screening and assessment enables hospitalists and other providers to identify high-need individuals and match services and delivery models to needs, whether it be respite care for an exhausted and overwhelmed family caregiver or a home protocol for managing recurrent dyspnea crises for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This process improves the quality of care and quality of life, and in doing so, prevents the need for costly crisis care.

Reducing Readmissions

By identifying patients in need of extra symptom management support, or those at a turning point requiring discussion about achievable priorities for care, hospitalists can avert crises for patients earlier in the disease trajectory either by managing the patient’s palliative needs themselves or by connecting patients with specialty palliative care services as needed. This leads to a better quality of life (and survival in some studies) for both patients and their families1,3,5 and reduces unnecessary emergency department (ED) and hospital use.12 Hospitalists providing palliative care can also reduce readmissions by improving care coordination, including clinical communication and medication reconciliation after discharge.13

A 2015 Harvard Business Review study found that the quality of communication in the hospital is the strongest independent predictor of readmissions when combined with process-of-care improvements, such as standardized patient screening and assessment of family caregiver capacity.14 While medical education prepares physicians to deliver evidence-based medical care, it currently offers little to no training in communication skills, despite mounting evidence that this is a critical component of quality healthcare.

Cost Savings

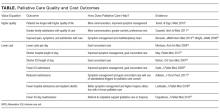

Hospital palliative care teams are associated with significant hospital cost savings that result from aligning care with patient priorities, leading, in turn, to reduced nonbeneficial hospital imaging, medications, procedures, and length of stay.15 See the table16,17 for examples of cost and quality outcomes of specialist palliative care provision and evidence supporting each outcome.18-25

Multiple studies consistently demonstrate that inpatient palliative care teams reduce hospital costs.26 One randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of an inpatient palliative care service found that patients who received care from the palliative care team reported greater satisfaction with their care, had fewer intensive care unit admissions, had more advanced directives at hospital discharge, longer hospice length of stay, and lower total healthcare costs (a net difference of $6766 per patient).23

Research shows that the earlier palliative care is provided, the greater the impact on the subsequent course of care,27 suggesting that hospitalists who provide frontline palliative care interventions as early as possible in a seriously ill patient’s stay will be able to provide higher quality care with lower overall costs. Notably, the majority of research on cost savings associated with palliative care has focused on the impact of specialist palliative care teams, and further research is needed to understand the economic impact of primary palliative care provision.