Associations of Physician Empathy with Patient Anxiety and Ratings of Communication in Hospital Admission Encounters

BACKGROUND: Responding empathically when patients express negative emotion is a recommended component of patient-centered communication.

OBJECTIVE: To assess the association between the frequency of empathic physician responses with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length during hospital admission encounters.

DESIGN: Analysis of coded audio-recorded hospital admission encounters and pre- and postencounter patient survey data.

SETTING: Two academic hospitals.

PARTICIPANTS: Seventy-six patients admitted by 27 attending hospitalist physicians.

MEASUREMENTS: Recordings were transcribed and analyzed by trained coders, who counted the number of empathic, neutral, and nonempathic verbal responses by hospitalists to their patients’ expressions of negative emotion. We developed multivariable linear regression models to test the association between the number of these responses and the change in patients’ State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S) score pre- and postencounter and encounter length. We used Poisson regression models to examine the association between empathic response frequency and patient ratings of the encounter.

RESULTS: Each additional empathic response from a physician was associated with a 1.65-point decline in the STAI-S anxiety scale (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). Frequency of empathic responses was associated with improved patient ratings for covering points of interest, feeling listened to and cared about, and trusting the doctor. The number of empathic responses was not associated with encounter length (percent change in encounter length per response 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%).

CONCLUSIONS: Responding empathically when patients express negative emotion was associated with less patient anxiety and higher ratings of communication but not longer encounter length.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Admission to a hospital can be a stressful event,1,2 and patients report having many concerns at the time of hospital admission.3 Over the last 20 years, the United States has widely adopted the hospitalist model of inpatient care. Although this model has clear benefits, it also has the potential to contribute to patient stress, as hospitalized patients generally lack preexisting relationships with their inpatient physicians.4,5 In this changing hospital environment, defining and promoting effective medical communication has become an essential goal of both individual practitioners and medical centers.

Successful communication and strong therapeutic relationships with physicians support patients’ coping with illness-associated stress6,7 as well as promote adherence to medical treatment plans.8 Empathy serves as an important building block of patient-centered communication and encourages a strong therapeutic alliance.9 Studies from primary care, oncology, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings indicate that physician empathy is associated with decreased emotional distress,10,11 improved ratings of communication,12 and even better medical outcomes.13

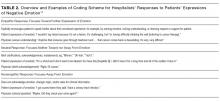

Prior work has shown that hospitalists, like other clinicians, underutilize empathy as a tool in their daily interactions with patients.14-16 Our prior qualitative analysis of audio-recorded hospitalist-patient admission encounters indicated that how hospitalists respond to patient expressions of negative emotion influences relationships with patients and alignment around care plans.17 To determine whether empathic communication is associated with patient-reported outcomes in the hospitalist model, we quantitatively analyzed coded admission encounters and survey data to examine the association between hospitalists’ responses to patient expressions of negative emotion (anxiety, sadness, and anger) and patient anxiety and ratings of communication. Given the often-limited time hospitalists have to complete admission encounters, we also examined the association between response to emotion and encounter length.

METHODS

We analyzed data collected as part of an observational study of hospitalist-patient communication during hospital admission encounters14 to assess the association between the way physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient anxiety, ratings of communication in the encounter, and encounter length. We collected data between August 2008 and March 2009 on the general medical service at 2 urban hospitals that are part of an academic medical center. Participants were attending hospitalists (not physician trainees), and patients admitted under participating hospitalists’ care who were able to communicate verbally in English and provide informed consent for the study. The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved the study; physician and patient participants provided written informed consent.

Enrollment and data collection has been described previously.17 Our cohort for this analysis included 76 patients of 27 physicians who completed encounter audio recordings and pre- and postencounter surveys. Following enrollment, patients completed a preencounter survey to collect demographic information and to measure their baseline anxiety via the State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S), which assesses transient anxious mood using 20 items answered on a 4-point scale for a final score range of 20 to 80.10,18,19 We timed and audio-recorded admission encounters. Encounter recordings were obtained solely from patient interactions with attending hospitalists and did not take into account the time patients may have spent with other physicians, including trainees. After the encounter, patients completed postencounter surveys, which included the STAI-S and patients’ ratings of communication during the encounter. To rate communication, patients responded to 7 items on a 0- to 10-point scale that were derived from previous work (Table 1)12,20,21; the anchors were “not at all” and “completely.” To identify patients with serious illness, which we used as a covariate in regression models, we asked physicians on a postencounter survey whether or not they “would be surprised by this patient’s death or admission to the ICU in the next year.”22

We considered physician as a clustering variable in the calculation of robust standard errors for all models. In addition, we included in each model covariates that were associated with the outcome at P ≤ 0.10, including patient gender, patient age, serious illness,22 preencounter anxiety, encounter length, and hospital. We considered P values < 0.05 to be statistically significant. We used Stata SE 13 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.