A Randomized Controlled Trial of a CPR Decision Support Video for Patients Admitted to the General Medicine Service

BACKGROUND: Patient preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are important, especially during hospitalization when a patient’s health is changing. Yet many patients are not adequately informed or involved in the decision-making process.

OBJECTIVES: We examined the effect of an informational video about CPR on hospitalized patients’ code status choices.

DESIGN: This was a prospective, randomized trial conducted at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Minnesota.

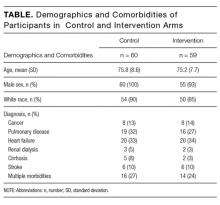

PARTICIPANTS: We enrolled 119 patients, hospitalized on the general medicine service, and at least 65 years old. The majority were men (97%) with a mean age of 75.

INTERVENTION: A video described code status choices: full code (CPR and intubation if required), do not resuscitate (DNR), and do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI). Participants were randomized to watch the video (n = 59) or usual care (n = 60).

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcome was participants’ code status preferences. Secondary outcomes included a questionnaire designed to evaluate participants’ trust in their healthcare team and knowledge and perceptions about CPR.

RESULTS: Participants who viewed the video were less likely to choose full code (37%) compared to participants in the usual care group (71%) and more likely to choose DNR/DNI (56% in the video group vs. 17% in the control group) (P < 0.00001). We did not see a difference in trust in their healthcare team or knowledge and perceptions about CPR as assessed by our questionnaire.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalized patients who watched a video about CPR and code status choices were less likely to choose full code and more likely to choose DNR/DNI.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be difficult due to their association with end of life. The Patient Self Determination Act (H.R.4449 — 101st Congress [1989-1990]) and institutional standards mandate collaboration between care providers and patients regarding goals of care in emergency situations such as cardiopulmonary arrest. The default option is to provide CPR, which may involve chest compressions, intubation, and/or defibrillation. Yet numerous studies show that a significant number of patients have no code preference documented in their medical chart, and even fewer report a conversation with their care provider about their wishes regarding CPR.1-3 CPR is an invasive and potentially painful procedure with a higher chance of failure than success4, and yet many patients report that their provider did not discuss with them the risks and benefits of resuscitation.5,6 Further highlighting the importance of individual discussions about CPR preferences is the reality that factors such as age and disease burden further skew the likelihood of survival after cardiopulmonary arrest.7

Complicating the lack of appropriate provider and patient discussion of the risks and benefits of resuscitation are significant misunderstandings about CPR in the lay population. Patients routinely overestimate the likelihood of survival following CPR.8,9 This may be partially due to the portrayal of CPR in the lay media as highly efficacious.10 Other factors known to prevent effective provider-and-patient discussions about CPR preferences are providers’ discomfort with the subject11 and perceived time constraints.12

Informational videos have been developed to assist patients with decision making about CPR and have been shown to impact patients’ choices in the setting of life-limiting diseases such as advanced cancer,13-14 serious illness with a prognosis of less than 1 year,15 and dementia.16 While discussion of code status is vitally important in end-of-life planning for seriously ill individuals, delayed discussion of CPR preferences is associated with a significant increase in the number of invasive procedures performed at the end of life, increased length of stay in the hospital, and increased medical cost.17 Despite clear evidence that earlier discussion of resuscitation options are valuable, no studies have examined the impact of a video about code status options in the general patient population.

Here we present our findings of a randomized trial in patients hospitalized on the general medicine wards who were 65 years of age or older, regardless of illness severity or diagnosis. The video tool was a supplement for, rather than a replacement of, standard provider and patient communication about code preferences, and we compared patients who watched the video against controls who had standard discussions with their providers. Our video detailed the process of chest compressions and intubation during CPR and explained the differences between the code statuses: full code, do not resuscitate (DNR), and do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI). We found a significant difference between the 2 groups, with significantly more individuals in the video group choosing DNR/DNI. These findings suggest that video support tools may be a useful supplement to traditional provider discussions about code preferences in the general patient population.

METHODS

We enrolled patients from the general medicine wards at the Minneapolis VA Hospital from September 28, 2015 to October 23, 2015. Eligibility criteria included age 65 years or older, ability to provide informed consent, and ability to communicate in English. Study recruitment and data collection were performed by a study coordinator who was a house staff physician and had no role in the care of the participants. The medical charts of all general medicine patients were reviewed to determine if they met the age criteria. The physician of record for potential participants was contacted to assess if the patient was able to provide informed consent and communicate in English. Eligible patients were approached and informed consent was obtained from those who chose to participate in the study. After obtaining informed consent, patients were randomized using a random number generator to the intervention or usual-care arm of the study.

Those who were assigned to the intervention arm watched a 6-minute long video explaining the code-preference choices of full code, DNR, or DNR/DNI. Full code was described as possibly including CPR, intubation, and/or defibrillation depending on the clinical situation. Do not resuscitate was described as meaning no CPR or defibrillation but possible intubation in the case of respiratory failure. Do not resuscitate/do not intubate was explained as meaning no CPR, no defibrillation, and no intubation but rather permitting “natural death” to occur. The video showed a mock code with chest compressions, defibrillation, and intubation on a mannequin as well as palliative care specialists who discussed potential complications and survival rates of inhospital resuscitation.

The video was created at the University of Minnesota with the departments of palliative care and internal medicine (www.mmcgmeservices.org/codestat.html). After viewing the video, participants in the intervention arm filled out a questionnaire designed to assess their knowledge and beliefs about CPR and trust in their medical care providers. They were asked to circle their code preference. The participants’ medical teams were made aware of the code preferences and were counseled to discuss code preferences further if it was different from their previously documented code preference.

Participants in the control arm were assigned to usual care. At the institution where this study occurred, a discussion about code preferences between the patient and their medical team is considered the standard of care. After informed consent was obtained, participants filled out the same questionnaire as the participants in the intervention arm. They were asked to circle their code status preference. If they chose to ask questions about resuscitation, these were answered, but the study coordinator did not volunteer information about resuscitation or intervene in the medical care of the participants in any way.

All participants’ demographic characteristics and outcomes were described using proportions for categorical variables and means ± standard deviation for continuous variables. The primary outcome was participants’ stated code preference (full code, DNR, or DNR/DNI). Secondary outcomes included comparison of trust in medical providers, resuscitation beliefs, and desire for life-prolonging interventions as obtained from the questionnaire.

We analyzed code preferences between the intervention and control groups using Fisher exact test. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare questionnaire responses between the 2 groups. All reported P values are 2-sided with P < 0.05 considered significant. The project originally targeted a sample size of 194 participants for 80% power to detect a 20% difference in the code preference choices between intervention and control groups. Given the short time frame available to enroll participants, the target sample size was not reached. Propitiously, the effect size was greater than originally expected.