Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services

Providing care to “very important person” (VIP) patients can pose unique moral and value-based challenges for providers. No studies have examined VIP services in the inpatient setting. Through a multi-institutional survey of hospitalists, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior surrounding the care of VIP patients. A significant proportion of respondents reported feeling pressured by patients, family members, and hospital representatives to provide unnecessary care to VIP patients. Based on self-reported perceptions, as well as case-based questions, we also found that the VIP status of a patient may impact physician clinical decision-making related to unnecessary medical care. Additional studies to quantify the use of VIP services and its effect on cost, resource availability, and patient-specific outcomes are needed. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:177-179. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

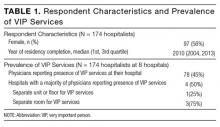

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

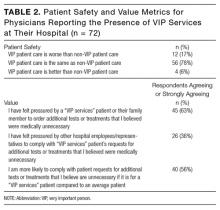

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).