Practical symptom-based evaluation of chronic constipation

Alarm features to look for; distinguishing primary from secondary disorder

- A symptom-based approach is the best means for diagnosing chronic constipation. Extensive diagnostic testing is seldom necessary unless alarm features are present (C).

- Encourage routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older (C).

When a patient tells you she is constipated, what does she really mean? You would think that a report so common about a complaint so universal would be immediately clear. But, in fact, there is no standard, widely accepted definition.

Researchers define constipation by diagnostic criteria (eg, Rome II).1

Recommendation grades based on the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force are presented on our web site (TABLE W1),4 as are the strength of recommendations taxonomy (SORT) grades for evidence (TABLE W2).5

Methods

References were selected by searching Medline and InfoRetriever using the terms constipation or chronic constipation and socioeconomics, prevalence, impact, treatment(s), patient unmet needs, patient needs, and definition. Articles from 1994 to November 2005 were included. Searches were restricted to manuscripts written in English and to those examining constipation in adults (aged 18 and older).

The focus of this article is on the North American population. A note-worthy limitation is that, although references for prevalence and socioeconomic impact are recent, most statistics in these references are from data more than 10 years old.

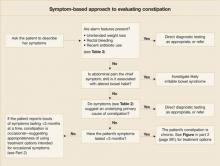

Using a symptom-based evaluation

The first step in this evaluation (FIGURE) is to ask the patient to clearly describe her symptoms.

FIGURE

Symptom-based approach to evaluating constipation

Helpful aids in assessing symptoms

The Rome II criteria (TABLE 1), developed by a panel of experts, are one frame of reference in which to assess a patient’s symptoms.1

Recently, to capture a more clinically relevant definition, the American College of Gastroenterology’s Chronic Constipation Task Force described constipation as a symptom-based disorder characterized by unsatisfactory defecation—infrequent stool or difficult stool passage, including straining, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stool, increased time to passing stool, use of manual maneuvers, or sense of difficulty passing stool (TABLE 1).4

TABLE 1

Definitions of chronic constipation

| ROME II DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION |

Constipation is defined by the presence of 2 or more of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months:

|

| AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY CHRONIC CONSTIPATION TASK FORCE |

| Constipation is a symptom-based disorder manifesting as unsatisfactory defecation and characterized by infrequent stool, difficult passage of stool (including straining, a sense of difficulty passing stool, prolonged time to bowel movement, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool), or both. Chronic constipation is defined as the presence of these symptoms for at least 3 months. |

| Sources: For Rome II: Thompson et al, Gut 19991; for ACG: Brandt et al, Am J Gastroenterol 2005.4 |

Specifics to look for in history and physical

Get a thorough account of the patient’s medical and surgical history, the family’s history, and medications currently used for other conditions (TABLE 2).

Ask about medications or maneuvers the patient has tried as constipation remedies, and consider potential reasons for ineffectiveness of medications. For instance, patients often do not take enough of an agent or do not give it enough time to work.

In the physical examination, be sure to include a digital rectal exam (looking for presence of skin tags, hemorrhoids, masses, etc).

Are alarm features present? Symptoms that are red flags suggestive of organic disease include rectal bleeding, symptom onset in patients older than 50 years, family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and key laboratory abnormalities (eg, anemia, leukocytosis), among others (TABLE 3).4 Such symptoms of course necessitate directed evaluation of the potential underlying cause.

Clues to primary or secondary constipation. Findings from the physical examination and patient history may also help distinguish between constipation that is primary (no known cause) and that which is secondary to a physiologic disorder (eg, hemorrhoids, strictures, anal fissure), medication (eg, antidepressants, anti-spasmodics), or lifestyle habits (eg, inactivity, inadequate fiber and fluid intake) (TABLE 2).6-11

When abdominal pain is the chief symptom. If the patient reports abdominal pain, explore the possibility of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). Symptom overlap between IBS-C and chronic constipation is common and includes hard, lumpy stools, straining, and feelings of incomplete evacuation. Abdominal pain is the main distinguishing feature.1