Causes of peripheral neuropathy: Diabetes and beyond

Leg paresthesias can be challenging to evaluate because of the varied causes and clinical presentations. This diagnostic guide with at-a-glance tables can help.

› When evaluating a patient with lower extremity numbness and tingling, order fasting blood glucose, vitamin B12 level with methylmalonic acid, and either serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) or immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) because these test have a high diagnostic yield. C

› Obtain SPEP or IFE when evaluating all patients over age 60 with lower extremity paresthesias. C

› Consider prescribing pregabalin for treating painful paresthesias because strong evidence supports its use; the evidence for gabapentin, sodium valproate, amitriptyline, venlafaxine, and duloxetine is moderate. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Sally G, age 46, has been experiencing paresthesias for the past 3 months. She says that when she is cycling, the air on her legs feels much cooler than normal, with a similar feeling in her hands. Whenever her hands or legs are in cool water, she says it feels as if she’s dipped them into an ice bucket. Summer heat makes her skin feel as if it's on fire, and she’s noticed increased sweating on her lower legs. She complains of itching (although she has no rash) and she’s had intermittent tingling and burning in her toes. On neurologic exam, she demonstrates normal strength, sensation, reflexes, coordination, and cranial nerve function.

Case 2 › Jessica T, age 25, comes in to see her family physician because she’s been experiencing numbness in her right leg. It had begun with numbness of the right great toe about a year ago. Subsequently, the numbness extended up her foot to the lateral aspect of the lower leg with an accompanying burning sensation. Three months prior to this visit, she developed weakness in her right foot and toes. She denies any symptoms in her left leg, upper extremities, or face.

A neurologic exam of the upper extremities is normal. Ms. T also has normal cranial nerve function, and normal strength, sensation, and reflexes in the left leg. A motor exam of the right leg reveals normal strength in the hip flexors, hip adductors, hip abductors, and quadriceps. On the Medical Research Council scale, she has 4/5 strength in the hamstrings, 0/5 in the ankle dorsiflexors, 1/5 in the posterior tibialis, and 3/5 in the gastrocnemius. She has a normal right patellar reflex, and an ankle jerk reflex and Babinski sign are absent. She has reduced sensation on the posterior and lateral portions of the right leg and the entire foot. Sensation is preserved on the medial side of the right lower leg and anterior thigh. She has right-sided steppage gait.

If these 2 women were your patients, how would you proceed with their care?

Paresthesias such as numbness and tingling in the lower extremities are common complaints in family medicine. These symptoms can be challenging to evaluate because they have multiple potential etiologies with varied clinical presentations.1

A well-honed understanding of lower extremity anatomy and the location and characteristics of common complaints is essential to making an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan. This article discusses the tests to use when evaluating a patient who presents with lower extremity numbness and pain. It also describes the typical presentation and findings of several types of peripheral neuropathy, and how to manage them.

Parasthesias are often the result of peripheral neuropathy

While paresthesias can arise from disorders of the central or peripheral nervous system, this article focuses on paresthesias that are the result of peripheral neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy can be classified as mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathy, or polyneuropathy:

- Mononeuropathy is focal involvement of a single nerve resulting from a localized process such as compression or entrapment, as in carpal tunnel syndrome.1

- Multiple mononeuropathy (mononeuritis multiplex) results from damage to multiple noncontiguous nerves that can occur simultaneously or sequentially, as in vasculitic causes of neuropathy.1

- Polyneuropathy involves 2 or more contiguous nerves, usually symmetric and length-dependent, creating a “stocking-glove” pattern of paresthesias.1 Polyneuropathy affects longer nerves first, and thus, patients will initially complain of symptoms in their feet and legs, and later their hands. Polyneuropathy is most commonly seen in diabetes.

Possible causes of peripheral neuropathy include numerous anatomic, systemic, metabolic, and toxic conditions (TABLE 1).1,2

What's causing the neuropathy? The search for telltale clues

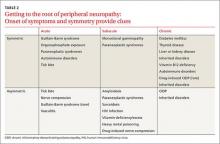

While obtaining the history, ask the patient about the presence of positive, negative, or autonomic neuropathic symptoms. Positive symptoms, which usually present first, are due to excess or inappropriate nerve activity and include cramping, twitching, burning, and tingling.3 Negative symptoms are due to reduced nerve activity and include numbness, weakness, decreased balance, and poor sensation. Autonomic symptoms include early satiety, constipation or diarrhea, impotence, sweating abnormalities, and orthostasis.3 The timing of onset, progression, and duration of such symptoms can give important diagnostic clues. For example, an acute onset of painful foot drop may indicate an inflammatory cause such as vasculitis, whereas slowly progressive numbness in both feet points toward a distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy, likely from a metabolic cause. Symmetry or asymmetry at presentation, as well as speed of progression of symptoms, can also significantly narrow the differential (TABLE 2).