The impact of patient education on consideration of enrollment in clinical trials

Background Advances in clinical care depend on well-designed clinical trials, yet the number of adults who enroll is suboptimal.

Objective To evaluate whether providing brief educational material about clinical trials would increase willingness to participate.

Methods From October 23, 2015, through November 12, 2015, 1511 adults in the United States completed an anonymized electronic survey in a single-group, cross-sectional-design study to measure the impression of and willingness to enroll in a hypothetical cancer clinical trial before and after reading brief educational material on the topic.

Results Participants had a worse impression of and were less likely to enroll in a clinical trial before reading the material. Most participants (86.2%) noted that the educational material was believable, easy to understand (84.8%), and included information that was new (81.5%). After reading the material, the overall impression of clinical trials improved (mean standard deviation [SD], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.35-0.50). This improved outlook was greater among participants with a lower level of completed education (Pinteraction < .001). Education level effect was no longer significant after reading the document. Similar results were observed for likeliness of enrolling.

Limitations The study was not randomized, so it is uncertain if the increase in interest and likelihood of enrolling in a clinical trial was solely a result of the intervention; the findings may not be generalizable to a cancer-only cohort, and only English-speaking participants were included.

Conclusion Participants were receptive of educational material and expressed greater interest and likelihood of enrolling in a clinical trial after reading the material. The information had a greater effect on those with less education, but it increased the willingness of all participants to enroll.

Funding/sponsorship Supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. Julien Mancini was supported through mobility grants from Fondation ARC (SAE20151203703), ADEREM, and Cancéropôle PACA (Mobilités-2015). He has also received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under the REA grant agreement, and he received PCOFUND-GA-2013-609102 through the PRESTIGE Programme coordinated by Campus France.

Accepted for publication April 19, 2018

Correspondence Paul J Sabbatini, MD; sabbatip@mskcc.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e81-e88

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0396

Submit a paper here

The low rate of participation in clinical trials is partly owing to the lack of awareness of these trials not only among potential participants but the US population as a whole.1 This lack of awareness, however, can be reversed. For example, findings from a single-institution observational study showed that systematically sending letters about clinical trial participation to all new lung cancer patients was associated with increased trial participation.2 More recently, a large, multicenter, randomized experiment showed that attitudes toward clinical trials were improved through preparatory education about clinical trials before a patient’s first oncologic visit.3

Such clinical trial education can be used before any medical diagnosis to increase clinical trial awareness in the general population. It may be advantageous to do so because people tend to process information more effectively during less stressful times.4 Clinical trial awareness in the US population has increased slightly over time, but in 2012, one study reported that 26% of its participants lacked general awareness about clinical trials.5

Comprehensive educational material, such as a multimedia psychoeducational intervention,6 a 28-video library,3 or a 160-page book,7 which have been proposed for oncology patients, may be too intensive for someone who is not immediately deciding whether to participate in a clinical trial. However, a simple, concise form of education might be preferable and appropriate to increase basic knowledge and awareness among the general population, especially among those who are less educated.8

,Our aim in the present study was to evaluate whether providing brief educational material about clinical trials would increase patient willingness to participate in these trials.

Methods

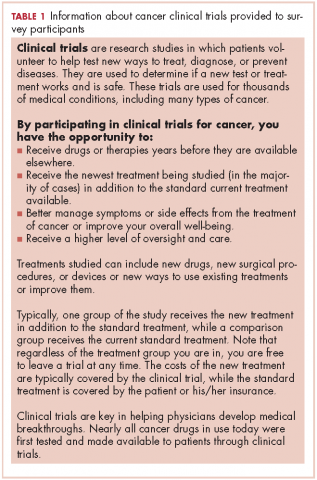

This is a single-group, cross-sectional design study in which all participants were administered the questions and the 240-word educational statement in the same order.

Sample

An electronic survey was conducted by Marketing and Planning Systems (the analytics practice of Kantar Millwardbrown) on behalf of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK). The survey included a national sample of 1011 participants and a local sample of 500 participants from the MSK catchment area (22 counties across the 5 boroughs of New York City, Long Island, southern New York State, northern New Jersey, and southwestern Connecticut).

Survey participants were aged 18 to 69 years in the national sample and 25 to 69 years in the local sample, representing 87% and 75% of the adult populations of those areas, respectively. Respondents who were or who had a family member currently working in the fields of news, advertising/marketing, or medical care were not surveyed. Participants were sourced from an online incentivized panel with millions of potential respondents representative of the US adult population.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire collected data on participant demographics and main medical history (including previous participation in a clinical trial), and asked questions about clinical trials, focusing on:

Analyses

Descriptive and bivariate statistical analyses of participants’ characteristics were weighted to ensure national representativeness for gender, age, ethnicity, and income. Mean standard deviation (SD) was computed for every quantitative variable. Categorical variables were expressed as proportions.

Student t tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare continuous variables, while chi-square tests were used to compare categorical data. Repeated measures ANOVAs were then used to determine the sociodemographic and medical characteristics associated with the impression of and willingness to enroll in a clinical trial before and after reading the educational material. The interaction between education level and time (pre- or postreading assessment) was tested to determine if the changes after reading the brief statement were different depending on education level.

All statistical analyses were 2-tailed and considered statistically significant at P < .05. Analyses were performed using SPSS PAWS Statistics 24 (IBM Inc, Armonk, New York). Effect sizes (standardized mean differences) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using the compute.es package for R 3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participants

From October 23, 2015, through November 12, 2015, 1511 US participants responded to the survey request, including 1507 respondents (99.7%) who reported their education level and are included in the analyses of this report. The mean age of the respondents was 43.5 years (SD, 4.6). More than half of the respondents (57.8%) reported a current medical condition, mainly cardiovascular (20.0%), arthritis (20.0%), or other type or chronic pain (20.0%), and 9.0% reported a cancer diagnosis (current, 2.9%; previous, 6.1%).

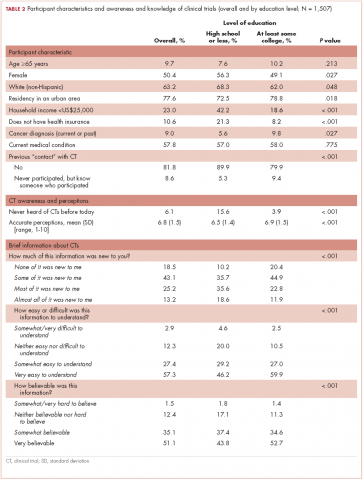

Participants who at most had completed high school (18.9%, including 1.4% who had never even attended high school) were more often white women, lived outside urban areas, had lower household income, and were less likely to have health care insurance (Table 2). They also reported a current or previous cancer diagnosis less often than those of similar age who had attended college.

Previous participation in a clinical trial was reported by 9.6% of participants. Most of the clinical trials (75.0%) were testing a new drug. Previous trial participants were more likely to be older than those who had not participated in trials (46.1 years [SD, 14.8] vs 43.3 [SD, 4.6], repectively; P = .033), have a current health condition (86.2% vs 54.8%; P < .001), and know another trial participant (39.9% vs 9.5%; P < .001).