Enhancing communication between oncology care providers and patient caregivers during hospice

Background When patients enroll in hospice, they and their close family and friends (ie, caregivers) often report feeling a sense of abandonment because of the break in routine communication with their oncology clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]).

Objective To assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients in hospice care.

Methods Caregivers of patients with cancer who enrolled in home hospice were eligible to participate. The intervention consisted of supportive phone calls from their oncology clinicians, an optional clinic visit, and a bereavement call. The primary outcome was feasibility, defined as >70% of caregivers receiving >50% of phone calls and >70% of caregivers completing >50% of questionnaires. We also assessed caregiver satisfaction with the supportive intervention, stress, decision regret, and perceptions of end-of-life care.

Results Of 38 eligible caregivers, 6 declined participation, 7 could not be reached, and 25 (81%) enrolled in the study. Of those, 22 caregivers were evaluable after 2 patients died before the intervention began and 1 caregiver withdrew. Oncology clinicians completed 164 of the expected 180 calls (91%) to caregivers. The majority of the calls were made by the RN or NP. Caregivers completed 78 of the expected 99 (79%) questionnaires. All of the caregivers received >50% of scheduled phone calls, and 73% completed >50% of the questionnaires. During exit interviews, caregivers reported satisfaction with the intervention.

Limitations Single-institution, small sample size

Conclusions This intervention proved feasible because caregivers received the majority of planned phone calls from oncology clinicians, completed the majority of study assessments, and reported satisfaction with the intervention. A randomized trial to evaluate the impact on caregiver outcomes is warranted.

Funding Supported on NIH T32CA071345

Accepted for publication January 31, 2018

Correspondence Jessica R Bauman, MD; Jessica.Bauman@fccc.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e72-e80.

2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0391

Related articles

The need for decision and communication aids: a survey of breast cancer survivors

Submit a paper here

Improving the delivery of end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer has become a priority in the United States.1,2 Quality metrics identifying the components of high-quality end-of-life care have focused on improved symptom management, decreased use of chemotherapy at the end of life, fewer hospitalizations, and increased use of hospice care. Patients and caregivers also consider good communication with the medical team to be a critical component of end-of-life care.3-5 Interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care are needed.

Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who receive hospice services report better quality of care and death than those receiving end-of-life care in other settings.6-9 However, the transition for patients from active cancer therapy delivered by their oncologists to end-of-life care delivered by a hospice care team can be abrupt. Patients and their caregivers often feel abandoned by oncology clinicians because of the lack of continuity of care and poor communication.10-13 Caregivers who note continued involvement and communication with their oncology clinicians experience a lower caregiving burden, report higher satisfaction with care, and recount a higher quality of death for their loved one.14-16 Therefore, interventions that prevent abrupt transitions in care from oncology to hospice by ensuring continued communication with oncology clinicians are needed to improve the quality of end-of-life care.17 Recent findings have shown that providing concurrent oncology and palliative care is not only feasible but beneficial for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.18-24 However, there is no standard of care for the involvement of oncology clinicians in the care of patients receiving hospice services and their families.

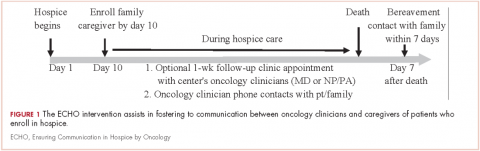

Although interventions may be needed, it could be challenging to deliver them given the multiple demands of caregiving during hospice and the lack of regular contact in clinic. We sought to assess the feasibility of an intervention, Ensuring Communication in Hospice by Oncology (ECHO), to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients who enroll in hospice. We also explored caregiver-reported outcomes during hospice care, including satisfaction with care, attitudes toward caregiving, stress, decision regret, and perception of the quality of patients’ end-of-life care.

Methods

Study design

During March 2014-June 2015, caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who enrolled in home hospice services were eligible to participate in the study at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. The Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved all methods and materials. The study opened with an enrollment goal of 30 participating caregivers. However, due to staff transitions, we closed the study early in June 2015 after 25 caregivers enrolled.

Participants

Caregivers of patients receiving care at the cancer center's thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological disease centers were eligible within 10 days after a patient’s enrollment in hospice. Five disease sites were selected to participate in the intervention. We defined caregivers as relatives or friends serving as the primary caregiver of the patient at home during hospice care. Other caregiver eligibility criteria included the ability to read and respond to questions in English or with a translator, access to a telephone and/or computer to communicate with oncology clinicians, and willingness to complete questionnaires. Caregivers were ineligible if the patient was participating in an ongoing palliative care trial.

To identify eligible caregivers, case managers from both the inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as the nurses based in participating disease centers, notified the research team of all patients referred to hospice. If the patient had received oncology care in one of our participating disease centers, the research team contacted their oncology clinician/s (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]) to inquire if the patient had an involved caregiver and to obtain permission to offer study participation. If the oncology clinician/s did not grant permission, we documented the reason. Otherwise, with permission, research staff contacted the caregiver by telephone to offer study participation and obtain verbal consent. We then sent participating caregivers a copy of the informed consent by mail or e-mail.

Intervention

The ECHO intervention consisted of: supportive phone calls from an oncology clinician to the caregiver; an optional clinic visit with the oncology clinician for the patient to address clinical questions or concerns that was offered during the initial telephone consent; a bereavement call to the participating caregiver (Figure 1). Initially, we designed the intervention to have phone calls occurring twice weekly until the patient died. However, 3 months after starting the study, we received feedback from oncology clinicians and caregivers that calls were too frequent, so we amended the protocol to include phone calls twice weekly for the first 2 weeks of the study and then weekly thereafter. Seven months into the study, we again decreased the number of phone calls to weekly for the first 4 weeks, every other week for 4 weeks, and then monthly until patient death. We informed caregivers of changes by e-mail.