Targeted therapies forge ahead in multiple breast cancer subtypes

Citation JCSO 2017;15(5):e277-e282

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0372

Submit a paper here

As our understanding of the biology of breast cancer has improved, treatment has become increasingly personalized. Targeted therapies continue to significantly improve patient outcomes in multiple subtypes, with several recent drug approvals. Here, we discuss some of these latest developments.

A disease of many faces

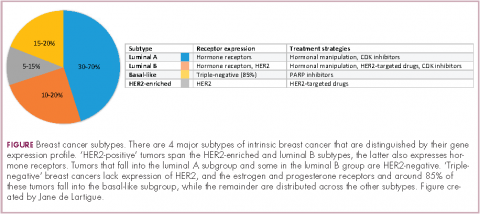

Clinically speaking, breast cancers can be divided into at least 5 subtypes on the basis of the genes they express (Figure 1). The luminal subtypes make up the largest proportion and are characterized by the expression of hormone receptor (HR) genes. Luminal A tumors are negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2; HER2-negative), whereas luminal B tumors often co-express the HER2 genes.1

The remainder of HER2-positive patients fall into the HER2-enriched category, in which HER2 expression is the defining characteristic. Basal-like tumors, meanwhile, represent the most heterogeneous subtype, overlapping to a large extent with tumors dubbed “triple-negative” because of their lack of either HER2 or ESR1 and PGR gene expression. The fifth subtype is known as normal breast-like and remains poorly characterized.

In recent years, there have been significant advancements in the genomic characterization of breast cancer that have begun to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the driver molecular mechanisms, which has helped to explain some of the limitations of current targeted approaches and to reveal new possible treatments, with a shift toward increasingly personalized strategies.2

HER2: what’s neu?

An estimated 18%-20% of breast tumors are HER2 positive, displaying amplification of the HER2/neu gene or overexpression of its protein product.3 Historically, HER2 positivity correlated with a highly aggressive and metastatic form of disease, conferring poor prognosis.4,5 The HER2-targeted monoclonal antibody (mAb), trastuzumab serves as a prime example of the power of personalized medicine. Evidence suggests that trastuzumab has altered the natural history of HER2-positive breast cancer, such that trastuzumab-treated patients with HER2-positive breast cancer now have a better prognosis than do patients with HER2-negative disease.6,7

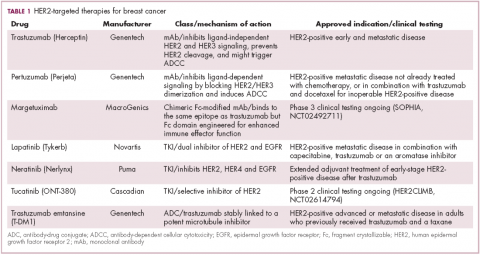

Several additional HER2-targeted drugs have joined trastuzumab on the market, including other mAbs, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), and an antibody–drug conjugate that combines the specificity of a mAb with the anti-tumor potency of a cytotoxic drug. These drugs have further improved patient outcomes in both early and advanced disease settings (Table 1).

The most recent regulatory approval was for neratinib, a potent TKI inhibiting all members of the HER protein family. On the basis of the phase 3 ExteNET study, neratinib was granted approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for extended adjuvant treatment of patients with HER2-positive, early-stage breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab. In a 5-year analysis of the study, invasive disease-free survival (DFS) was 90.4% with neratinib, compared with 87.9% with placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74; P = .017).8,9

The tide of advancements in HER2-targeted therapy looks set to continue in the coming years as potentially practice-changing data emerges from ongoing clinical trials and, as the patent on trastuzumab has expired, a number of biosimilars, such as MYL-1401O have the potential to help patients who may not have access to trastuzumab.10

One of the biggest remaining challenges is identifying drugs that can effectively treat patients with brain metastases because the blood–brain barrier presents an impediment to the delivery of effective concentrations of anticancer drugs. Initially, it was hoped that the small molecule inhibitors lapatinib and neratinib could cross the blood–brain barrier and may be more effective in patients with brain metastases, but that hypothesis has not borne out in randomized clinical trials.11

Tucatinib (ONT-380) has shown significant promise in this respect. In a phase 1 trial, ONT-380 had significant efficacy in patients with and without central nervous system metastases; the overall response rate (ORR) in the CNS was 36%. ONT-380 is also notable for its specificity for HER2, without significant inhibition of HER1 and EGFR, which could translate into a better toxicity profile.12

Doubling down on resistant tumors

Since the success of HER2-targeted therapy is limited by the development of resistance, there has been significant interest in assessing the potential of dual HER2 blockade, exploiting the unique mechanisms of action of different drugs in combination therapy, and ensuring more complete inhibition of the HER2 pathway. Although numerous different combinations have been tested, a double antibody combination has proved most effective.

In fact, dual HER2 targeting with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with chemotherapy has replaced a trastuzumab-chemotherapy regimen as the new standard of care in the metastatic setting. A 6-month improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) sealed FDA approval for the combination and in a recently published final analysis of the trial overall survival (OS) was also improved to a level unprecedented in the first-line setting.13,14The double antibody combination has also been successful in the neoadjuvant setting. Approval followed the results of the phase 2 NeoSphere trial, in which the combination was associated with a significant improvement in pathologic complete response (pCR) rate, a measure that acts as a surrogate for improved survival in the neoadjuvant setting. In a 5-year analysis of the NeoSphere trial, improved pCR did indeed translate into improved PFS and DFS.15,16

The results of the phase 3 APHINITY trial evaluating this combination in the adjuvant setting have been hotly anticipated. In a presentation at the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in June, the study authors reported that in 4,085 patients with operable HER2-positive disease, it significantly reduced the risk of disease recurrence or death compared with trastuzumab and chemotherapy alone.17

There is an ongoing effort to determine if it is possible to de-escalate treatment by removing the chemotherapy component. At least in the neoadjuvant setting, pCR rates in the chemotherapy-free arms of several studies suggest that a proportion of patients might benefit from this strategy15,18,19 and the challenge now is to identify them. To that end, the phase 2 PAMELA trial identified the HER2-enriched subtype as a strong predictor of response to neoadjuvant dual blockade (lapatinib and trastuzumab) without chemotherapy. The pCR rate was 40.6% for the combination in patients with the HER2-enriched subtype of breast cancer and only 10% in patients with non–HER2-enriched tumors.20