Demystifying the diagnosis and classification of lymphoma: a guide to the hematopathologist’s galaxy

JCSO 2017;15(1):43-48. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications. doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0328.

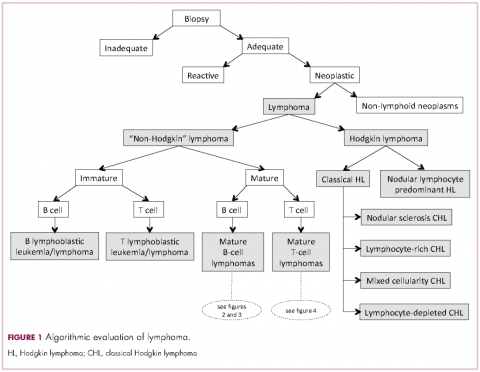

Lymphomas constitute a very heterogeneous group of neoplasms with diverse clinical presentations, prognoses, and responses to therapy. Approximately 80,500 new cases of lymphoma are expected to be diagnosed in the United States in 2017, of which about one quarter will lead to the death of the patient.1 Perhaps more so than any other group of neoplasms, the diagnosis of lymphoma involves the integration of a multiplicity of clinical, histologic and immunophenotypic findings and, on occasion, cytogenetic and molecular results as well. An accurate diagnosis of lymphoma, usually rendered by hematopathologists, allows hematologists/oncologists to treat patients appropriately. Herein we will describe a simplified approach to the diagnosis and classification of lymphomas (Figure 1).

Lymphoma classification

Lymphomas are clonal neoplasms characterized by the expansion of abnormal lymphoid cells that may develop in any organ but commonly involve lymph nodes. The fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues, published in 2008, is the official and most current guideline used for diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasms.2 The WHO scheme classifies lymphomas according to the type of cell from which they are derived (mature and immature B cells, T cells, or natural killer (NK) cells, findings determined by their morphology and immunophenotype) and their clinical, cytogenetic, and/or molecular features. This official classification is currently being updated3 and is expected to be published in full in 2017, at which time it is anticipated to include definitions for more than 70 distinct neoplasms.

,Lymphomas are broadly and informally classified as Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), based on the differences these two groups show in their clinical presentation, treatment, prognosis, and proportion of neoplastic cells, among others. NHLs are by far the most common type of lymphomas, accounting for approximately 90% of all new cases of lymphoma in the United States and 70% worldwide.1,2 NHLs are a very heterogeneous group of B-, T-, or NK-cell neoplasms that, in turn, can also be informally subclassified as low-grade (or indolent) or high-grade (or aggressive) according to their predicted clinical behavior. HLs are comparatively rare, less heterogeneous, uniformly of B-cell origin and, in the case of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, highly curable.1,2 It is beyond the scope of this manuscript to outline the features of each of the >70 specific entities, but the reader is referred elsewhere for more detail and encouraged to become familiarized with the complexity, challenges, and beauty of lymphoma diagnosis.2,3

Biopsy procedure

A correct diagnosis begins with an adequate biopsy procedure. It is essential that biopsy specimens for lymphoma evaluation be submitted fresh and unfixed, because some crucial analyses such as flow cytometry or conventional cytogenetics can only be performed on fresh tissue. Indeed, it is important for the hematologist/oncologist and/or surgeon and/or interventional radiologist to converse with the hematopathologist prior to and even during some procedures to ensure the correct processing of the specimen. Also, it is important to limit the compression of the specimen and the excessive use of cauterization during the biopsy procedure, both of which cause artifacts that may render impossible the interpretation of the histopathologic findings.

Given that the diagnosis of lymphoma is based not only on the cytologic details of the lymphoma cells but also on the architectural pattern with which they infiltrate an organ, the larger the biopsy specimen, the easier it will be for a hematopathologist to identify the pattern. In addition, excisional biopsies frequently contain more diagnostic tissue than needle core biopsies and this provides pathologists with the option to submit tissue fragments for ancillary tests that require unfixed tissue as noted above. Needle core biopsies of lymph nodes are increasingly being used because of their association with fewer complications and lower cost than excisional biopsies. However, needle core biopsies provide only a glimpse of the pattern of infiltration and may not be completely representative of the architecture. Therefore, excisional lymph node biopsies of lymph nodes are preferred over needle core biopsies, recognizing that in the setting of deeply seated lymph nodes, needle core biopsies may be the only or the best surgical option.

Clinical presentation

Accurate diagnosis of lymphoma cannot take place in a vacuum. The hematopathologist’s initial approach to the diagnosis of lymphoid processes in tissue biopsies should begin with a thorough review of the clinical history, although some pathology laboratories may not have immediate access to this information. The hematopathologist should evaluate factors such as age, gender, location of the tumor, symptomatology, medications, serology, and prior history of malignancy, immunosuppression or immunodeficiency in every case. Other important but frequently omitted parts of the clinical history are the patient’s occupation, history of exposure to animals, and the presence of tattoos, which may be associated with certain reactive lymphadenopathies.