The Daily Safety Brief in a Safety Net Hospital: Development and Outcomes

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

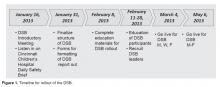

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.