Primary renal synovial sarcoma – a diagnostic dilemma

Accepted for publication October 5, 2018

Correspondence Yellala Amulya, MD; amulya.yellala@ahn.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(5):e202-e205

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0426

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

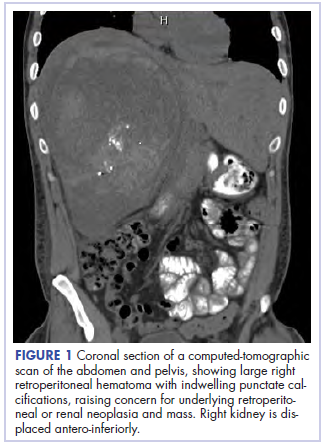

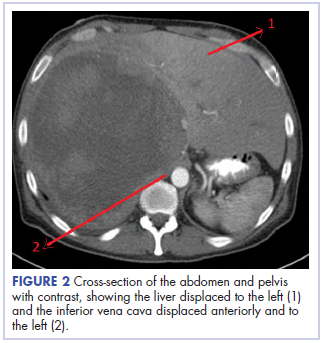

,Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

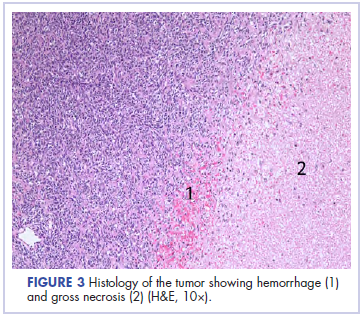

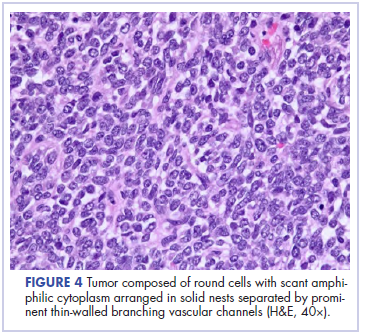

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.