Rhabdomyolysis Occurring After Use of Cocaine Contaminated With Fentanyl Causing Bilateral Brachial Plexopathy

Background: Rhabdomyolysis is caused by muscle overuse, trauma, prolonged immobilization, drugs, or toxins. As rhabdomyolysis progresses, swelling and edema can compress surrounding structures. Few cases of the phenomenon occurring as a sequela of substance use have been described.

Case Presentation: We present a 68-year-old male patient with rhabdomyolysis following use of crack cocaine contaminated with fentanyl. The patient had 0/5 strength bilaterally and bilateral absent reflexes in the upper extremities. Sensation was markedly decreased, as he was unable to feel temperature, pinprick sensation, or general touch. Creatine phosphokinase level was elevated at 21,292 IU/L. On magnetic resonance imaging, there was abnormal signal in the lower neck bilaterally. It is presumed that muscular edema resulted in partial narrowing of the thoracic outlet bilaterally with corresponding mass effect on the traversing brachial plexus.

Conclusions: This is the seventh case of brachial plexopathy secondary to rhabdomyolysis precipitated by opioid use that has been reported in the literature. Prospective studies should examine treatment for this condition.

The brachial plexus is a group of interwoven nerves arising from the cervical spinal cord and coursing through the neck, shoulder, and axilla with terminal branches extending to the distal arm.1 Disorders of the brachial plexus are more rare than other isolated peripheral nerve disorders, trauma being the most common etiology.1 Traction, neoplasms, radiation exposure, external compression, and inflammatory processes, such as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, have also been described as less common etiologies.2

Rhabdomyolysis, a condition in which muscle breakdown occurs, is an uncommon and perhaps underrecognized cause of brachial plexopathy. Rhabdomyolysis is often caused by muscle overuse, trauma, prolonged immobilization, drugs, or toxins. Substances indicated as precipitating factors include alcohol, opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines.3,4 As rhabdomyolysis progresses, swelling and edema can compress surrounding structures. Therefore, in cases of rhabdomyolysis involving the muscles of the neck and shoulder girdle, external compression of the brachial plexus can potentially cause brachial plexopathy. Rare cases of this phenomenon occurring as a sequela of substance use have been described.1,5-9 Few cases have been reported in the literature.

The following case report describes a patient who

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male patient with a history of polysubstance use disorder presented to the emergency department with complete loss of sensory and motor function of both arms. He had fallen asleep on his couch the previous evening with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position.

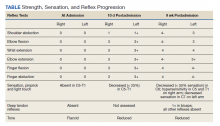

On admission, the patient presented with an agitated mental status. The patient presented with 0/5 strength bilaterally in the upper extremities (UEs) accompanied by numbness and tingling. Radial pulses were palpable in both arms. All UE reflexes were absent, but patellar reflex was intact bilaterally. On hospital day 2, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time and could provide a full history. The patient’s cranial nerves were intact with shoulder shrug testing mildly weak at 4/5 strength.

Serum electrolytes and glucose levels were normal. The creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was elevated at 21,292 IU/L. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and 32 mg/dL, respectively. Serum B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c levels were normal.

Due to the absence of evidence of spinal cord injury, presence of normal motor and sensory function of the lower extremities, an elevated CPK level, signal hyperintensities of the muscles of the shoulder girdle, and the patient’s history, the leading diagnosis at this time was brachial plexopathy secondary to focal rhabdomyolysis.

Over the next week, the patient regained some motor function of the left hand and some sensory function bilaterally. At 8 weeks postadmission, a nerve conduction study showed prolonged latencies in the median and ulnar nerves bilaterally. The following week, the patient reported pain in both shoulders (left greater than the right) as well as weakness of shoulder movement on the left greater than the right. There was pain in the right arm throughout. On examination, there was improved function of the arms distal to the elbow, which was better on the right side despite the associated pain (Table). There was atrophy of the left scapular muscles, hypothenar eminence, and deltoid muscle. There was weakness of the left triceps, with slight fourth and fifth finger flexion. The patient was unable to elevate or abduct the left shoulder but could elevate the right shoulder up to 45°. Sensation was decreased over the right outer arm and left posterior upper arm, with hypersensitivity in the right medial upper and lower arm. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in the upper arm aside from the biceps reflex (1+). All reflexes of the lower extremities were normal. It is interesting to note the relative greater improvement on the right despite the edema found on initial imaging being more prominent on the right.