Brief Review of Major Depressive Disorder for Primary Care Providers

Although a common condition in the general population, major depressive disorder (MDD) is even more prevalent among patients receiving medical care. Its early recognition and successful treatment have significant implications in all fields of medicine, and the predominant burden of treatment falls on primary care providers (PCPs). The prevalence of MDD over 12 months is about 6.6%; lifetime risk is about 16.6%.1,2 About 50% of depressive episodes are rated severe or higher level. Of those having a depressive episode lasting 1 year, only 51% will seek medical help, and only 42% of these will receive adequate treatment.3 The illness is present across cultures and socioeconomic strata, although the actual rates vary. Women have about a 2-fold higher rate of MDD than do men.4

The illness can vary from mild to severe. Primary care providers usually provide treatment for patients who are at the mild-to-moderate end of the spectrum; more severely ill patients are likely to require consulting with mental health specialists. Patients who have 1 episode of MDD have a 50% chance of having a second episode during their lifetime. After a second episode, the risk of another episode rises to about 80%.5 After a third episode, it is presumed patients will continue to have subsequent episodes, because the risk rises to 90%. Among patients with MDD, about 35% will have a chronic, relapsing pattern of illness.6 Because of a relative shortage of specialty mental health providers in many areas served by federal practitioners, it is important to maximize the impact of a patient’s primary care team in treating this common and persistent illness.

Morbidity from MDD includes dysfunction in all spheres of life: Difficulties with work, home life, self-care, medication adherence, and mental health are all encountered. Although a minority of patients with depression will attempt or complete suicide, depression is a major predictor of suicide risk. However, it is a modifiable risk factor with successful treatment. Among the general population, the reported risk of suicide is about 11.5 per 100,000 per year.7 Among patients with psychiatric illness, the rate is higher.

Many patients treated through the federal system have been identified as having a risk of suicide higher than that of the general population. These populations include veterans (41% to 61% above the national average); Native Americans aged 18 to 24 years (about 2 to 3 times the national average); and active-duty military (18.7 per 100,000 per year, 50% above the national average).8-10

Diagnosis

Several subtypes of MDD and associated depressive disorders exist. The diagnosis requires a constellation of criteria for diagnosis. Using the full criteria to make an MDD diagnosis may seem excessive, but its use is critical to guide sound treatment decisions (ie, past presence of manic or hypomanic episode, which would signify bipolar disorder, or psychotic symptoms that would dictate a different path and a referral to a psychiatrist). For example, an antidepressant given to a patient with a history of hypomania or mania can trigger a full manic episode with all the potential morbidity that mania entails. The presence of psychotic symptoms leads down a different treatment path that requires antipsychotic medication.

A major depressive episode includes the sine qua non of depressed mood or anhedonia (lack of experiencing or seeking pleasurable activities) and 3 to 4 associated criteria, including poor energy (often noted as “I just can’t seem to get moving”), insomnia/hypersomnia (usually middle or late insomnia) with difficulty concentrating (often seen as problems making decisions), increased sense of guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor agitation or retardation (often noted by the patient’s spouse), significant weight loss or gain (5%), and thoughts of death/dying or suicidal ideation. These must be present most days over the previous 2 weeks.1 The time duration criteria are important because some patients may seem very distressed during a visit but do not meet the criteria for depression or have the chronic depressive symptoms of MDD. Symptoms not meeting the full criteria may likely be noted as unspecified depressive disorder or dysthymia (now termed persistent depressive disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM 5]).1 There are no FDA-approved treatments for these disorders; however, in cases requiring treatment, the standard of practice would be the same as for MDD.

The more severe types of MDD are usually not subtle and would likely require an immediate referral to a mental health professional. These include the presence of melancholic features, such as severe anhedonia, or loss of reactivity to normally pleasurable things, and at least 3 of the following: (1) distinct quality of depressed mood that is characterized as different from serious loss (ie, death of a loved one); (2) worse depression in the morning; (3) late insomnia (waking 2+ hours early); (4) marked psychomotor agitation or retardation; (5) significant anorexia or weight loss; and (6) excessive and inappropriate guilt; or the presence of psychotic features, such as delusions or hallucinations. There are other subtypes of MDD that can be found in DSM 5.

Treatment

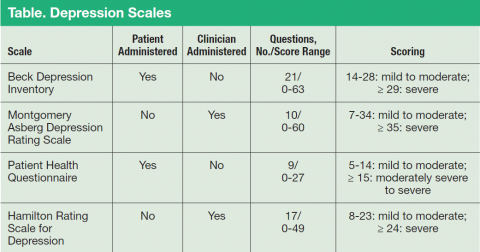

Major depressive disorder can be viewed as analogous to common illnesses, such as hypertension or diabetes, which are treated by a PCP; screening for depression should be systematically included as part of primary care services. The clear goal of treatment for any illness is elimination or reduction of symptoms so they no longer cause any significant problem for the patient. In MDD remission is the complete resolution of depressive symptoms. Response is considered a 50% reduction of MDD symptom severity as rated on various depression scales (Table). Because no objective physical measurements exist for assessing a patient’s depression, using a rating scale is necessary to monitor the severity of depressive symptoms and a patient’s response to treatment.

There are many validated depression scales, both clinician and patient administered. A patient-administered scale can save time and provide needed information; however, the questions of a clinician-administered scale can help screen for depression and improve a clinician’s sensitivity to a patient’s depression even if the patient does not bring up the subject. These scales are available on the Internet and include instructions for proper use. Benefits of the scales include giving clinicians data to discuss with patients and helping patients track their progress. For example, patients do not always recall how they were doing before they started taking medications, so the scales can help them measure the improvement.

Psychotherapies

As first-line treatment for patients with MDD, no clear benefit exists for medication over psychological therapy, specifically evidence-based therapies (EBTs).11,12 The best studied and known EBTs are cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (CBT-D) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). Both are brief, targeted therapies with clear rules and expectations as opposed to more traditional long-term therapies, such as insight-oriented psychotherapy. These therapies generally involve weekly meetings with a therapist for about 12 weeks. They both require the patient to do homework during the therapy period; therefore, it is important for the patient to be a willing participant in these treatments to receive the maximum benefit. Many patients prefer not taking medication for depression, so psychotherapy is an excellent option. It is widely believed, although without clear evidence at this time, that the combination of medications and EBT offers improved outcomes. There are no contraindications to combining antidepressant medication and EBT.