Hardware for the Heart: The Increasing Impact of Pacemakers, ICDs, and LVADs

Evaluating and treating patients with an automated implantable cardiac device requires both an understanding of the components and function of each device, as well as the associated complications.

Alicia S. Devine, JD, MD

Dr Devine is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The author reports no conflict of interest.

Heart disease affects a growing number of patients each year. The causes of heart disease are diverse, but whether the etiology is ischemic or structural, the disease often progresses to the point where patients are at risk for fatal dysrhythmias and heart failure. Treatment modalities for heart disease range from lifestyle modification and medical management to interventional reperfusion, and often involve the surgical implantation of devices designed to improve cardiac function and/or to detect and terminate lethal dysrhythmias.

Over the past two decades, the use of automated implantable cardiac devices (AICDs) such as pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) has increased significantly. From 1993 to 2009, nearly 3 million patients received permanent pacemakers in the United States; in 2009 alone, over 188,000 were placed. From 2006 to 2011 (the period for which the most recent data are available), approximately 850,000 patients had an AICD implanted. For the 20-month period running from April 2010 to December 2011, nearly 260,000 patients received the device. Finally, from 2006 through 2013, over 9,000 LVADs were placed. Like the other cardiac devices discussed, the frequency of use continues to increase, with 3,834 LVADs placed in just the first 9 months of 2013.

Emergency physicians are expected to be able to stabilize and manage patients with these devices who present to the ED. Care for these patients requires an understanding of the components and function of the different devices as well as their complications. All of the devices are subject to complications from infection, bleeding, migration, or fracture of the component parts, and, more ominously, complete failure of the device. While the current generation of cardiac devices are much smaller in size than their initial prototypes, they are more technically complex, and consultation with cardiology after initial stabilization is recommended.

Cardiac Hardware

Management of the Patient With an Implanted Pacemaker

Martin Huecker, MD

Thomas Cunningham, MD

Dr Huecker is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Dr Cunningham is chief resident, department of emergency medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Cardiac pacing was conceived in 1899, and the first successful pacemaker was implanted in 1960.1,2 New concepts and evolution of design have made pacemakers increasingly complex. Over the last decade, the rate of implantation has grown by over 50%.3 At the forefront of cardiac care, today’s EP must be proficient in the care of patients with cardiac pacemakers.

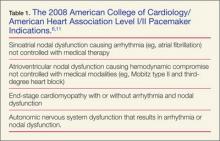

The pacemaker consists of a generator and its leads. The generator produces an electrical impulse that travels down the leads to depolarize myocardial tissue.4 A pacemaker corrects abnormal heart rhythms, using these electrical pulses to induce a novel sinus rhythm.5,6Table 1 summarizes the 2008 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Level I/II indications for pacemaker placement.

Permanent pacing involves fluoroscopic placement of leads into a chamber(s) of the heart. The generator is implanted most commonly in the left subcutaneous chest.7-9 A single-chamber pacemaker’s leads are located in either the right atrium or ventricle. Dual-chamber pacemakers function with one electrode in the atrium and one in the ventricle. A biventricular pacemaker, also known as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) paces both ventricles via the septal walls.4,7,10

All pacemaker patients need prompt identification of the device manufacturer.8 Patients should carry identification cards. Chest X-ray may identify the device and will give information as to the location and structural integrity of wires. Interrogation should generally be performed in all patients and will provide valuable information such as battery status, current mode, rate, past rhythms, parameters to detect malignant rhythms, and therapeutic settings.4

Evaluation of the patient with a pacemaker begins with a detailed history and physical examination, including any complications involving the device. Clinicians should ask about pacemaker-related symptoms—ie, palpitations, light-headedness, syncope, or changes in exercise tolerance.3 As with all chest pain complaints in the ED, addressing abnormal vital signs and identification of myocardial infarction (MI) must precede other considerations.

Myocardial Infarction in the Pacemaker Patient

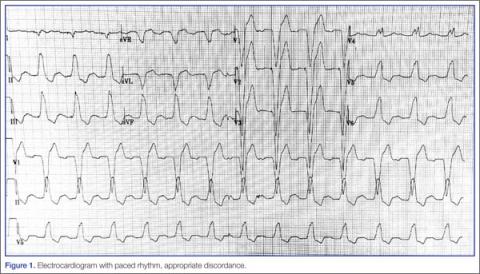

Because of the underlying rhythm induced by the cardiac pacemaker stimulation, acute coronary occlusion can be subtle.12 Since the pacemaker depolarizes the right ventricle, the delay in left ventricular depolarization is seen as left bundle branch block (LBBB) on electrocardiogram (ECG).13,14Figure 1 shows an ECG demonstrating paced rhythm and appropriate discordance, while the ECG in Figure 2 demonstrates acute coronary occlusion. Therefore, identification of coronary occlusion in the paced patient is done using the following Sgarbossa criteria: