Acute Submandibular Sialadenitis

Case

A 21-year-old woman presented to the ED with pain and swelling on the right side of her neck. She stated the pain started earlier that morning and worsened when she ate or swallowed. The patient denied a recent or remote history of drooling, voice changes, or neck swelling. She reported no fevers, chills, or any other complaints, and had no pertinent medical history—specifically, no history of recent dental work. Her surgical history included tonsillectomy and cholecystectomy. There was no family history of diabetes, thyroid disease, autoimmune disease, or any other diseases. The patient stated that she was not on any prescription or over-the-counter medications. Regarding her social history, she denied past or cu

Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 124/63 mm Hg (sitting); heart rate, 73 beats/min; respiratory rate, 15 breaths/min; and temperature, 98°F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. On clinical examination, pain was noted in the patient’s right submandibular area and was tender to palpation. The swelling extended to the angle of the mandible posteriorly (Figure 1a and 1b). There was no erythema or increased surface temperature to suggest overlying cellulitis. The oral examination showed no evidence of dental infection, angioedema, or Ludwig angina. The pharynx was normal in appearance. The otological examination was unremarkable, and there was no evidence of mastoiditis.

Laboratory evaluation included a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic profile (BMP), and rapid streptococcal test (RST). The results of the patient’s CBC revealed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 11.1 x 109/L; the BMP was unremarkable; and the RST was negative.

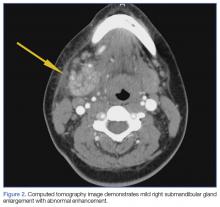

A soft tissue neck computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was obtained, which revealed mild right submandibular gland enlargement with abnormal enhancement (Figure 2). Stranding was also noted in the right submandibular space along with thickening of the right platysma muscle, and few surrounding lymph nodes were prominent (Figure 3). The findings were consistent with acute submandibular sialadenitis.

The patient received intravenous (IV) normal saline for hydration and IV ketorolac for analgesia, as well as an initial dose of oral amoxicillin/clavulanate 875/125 mg. At discharge, she was given a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanate 875/125 mg with instructions to follow-up with her primary care physician and otolaryngologist within 2 days. The patient did well on follow-up, and her symptoms resolved within a few days of discharge.

Discussion

Comparatively little has been published on acute submandibular sialadenitis over the past three decades, and much of that which is cited in the literature comes from a rather small pool of case reports.1 In a literature review, Raad et al1 noted, “Pertinent literature on [this] subject includes case reports but no studies describing the microbial and clinical characteristics of this disease.” Further, many of the published case reports describe neonatal presentations of submandibular sialadenitis, the incidence of which is rare in this patient population.2-4

Submandibular and Parotid Glands

The submandibular gland is the second largest salivary gland, the parotid gland being the largest. The duct of the salivary gland, the Wharton’s duct, opens under the tongue in the area of the lingual frenulum. Ductal obstruction is more frequently seen with the submandibular gland than with the parotid gland.1 The reason for this is unclear, but may be related to several factors. One factor may be that, unlike the Stenson’s duct of the parotid gland, the Wharton’s duct does not pass through a muscle; thus, there is no muscular massage supporting the movement of secretion, as there is with buccinator muscle massage of Stenson’s duct. In addition, submandibular saliva is more viscous than parotid saliva due to its higher protein content and higher concentration of calcium phosphate.1

Etiology

Submandibular gland obstruction can occur in the absence of infection. Noninfectious cases typically present with pain upon eating and swallowing. A bacterial infectious etiology is associated with odynophagia, but also includes persistent pain and tenderness. This presents as pain associated with eating. Bacterial infection of the submandibular gland adds the element of persistent pain, associated with such features as tenderness. In addition, purulent discharge from the Wharton’s duct may be present in infectious cases, and accompanied by fever, chills, and an elevated WBC.1