Lip Reconstruction After Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Guide on Flaps

The lips are commonly affected by skin cancer because of increased sun exposure over time. Even with early detection, many of these skin cancers require surgical removal with subsequent reconstruction. Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred method of treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancers of the lip, as it has the lowest recurrence rates and allows for the maximum preservation of healthy tissue. After surgery, the remaining lip defect often requires reconstruction with skin grafts or a local cutaneous or myocutaneous flap. There are several local flap reconstruction options available, and some may be used in combination for more complex defects. We provide a succinct review of commonly utilized flaps and outline their indications, risks, and benefits.

Practice Points

- Even with early detection, many skin cancers on the lips require surgical removal with subsequent reconstruction.

- There are several local flap reconstruction options available, and some may be used in combination for more complex defects.

- The most suitable technique should be chosen based on tumor location, tumor stage or depth of invasion (partial or full thickness), and preservation of function and aesthetics.

The lip is commonly affected by skin cancer because of increased sun exposure and actinic damage, with basal cell carcinoma typically occurring on the upper lip and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip. The risk for metastatic spread of SCC on the lip is higher than cutaneous SCC on other facial locations but lower than SCC of the oral mucosa.1,2 If the tumor is operable and the patient has no contraindications to surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred treatment, as it allows for maximal healthy tissue preservation and has the lowest recurrence rates.1-3 Once the tumor is removed and margins are confirmed to be negative, one must consider the options for defect closure, including healing by secondary intention, primary/direct closure, full-thickness skin grafts, local flaps, or free flaps.4 Secondary intention may lead to wound contracture and suboptimal functional and cosmetic outcomes. Primary wedge closure can be utilized for optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes when the defect involves less than one-third of the horizontal width of the vermilion. For larger defects, the surgeon must consider a flap or graft. Skin grafts are less favorable than local flaps because they may have different skin color, texture, and hair-bearing properties than the recipient area.3,5 In addition, grafts require a separate donor site, which means more pain, recovery time, and risk for complications for the patient.3 Free flaps similarly utilize tissue and blood supply from a donor site to repair major tissue loss. Radial forearm free flaps commonly are used for large lip defects but are more extensive, risky, and costly compared to local flaps for smaller defects under local anesthesia or nerve blocks.6,7 With these considerations, a local lip flap often is the most ideal repair method.

When performing a local lip flap, it is important to consider the functional and aesthetic aspects of the lips. The lower face is more susceptible to distortion and wound contraction after defect repair because it lacks a substantial supportive fibrous network. The dynamics of opposing lip elevator and depressor muscles make the lips a visual focal point and a crucial structure for facial expression, mastication, oral continence, speech phonation, and mouth opening and closing.2,4,8,9 Aesthetics and symmetry of the lips also are a large part of facial recognition and self-image.9

Lip defects are classified as partial thickness involving skin and muscle or full thickness involving skin, muscle, and mucosa. Partial-thickness wounds less than one-third the width of the horizontal lip can be repaired with a primary wedge resection or left to heal by secondary intention if the defect only involves the superficial vermilion.2 For defects larger than one-third the width of the horizontal lip, local flaps are favored to allow for closely matched skin and lip mucosa to fill in the defect.9 Full-thickness defects are further classified based on defect width compared to total lip width (ie, less than one-third, between one-third and two-thirds, and greater than two-thirds) as well as location (ie, medial, lateral, upper lip, lower lip).2,10

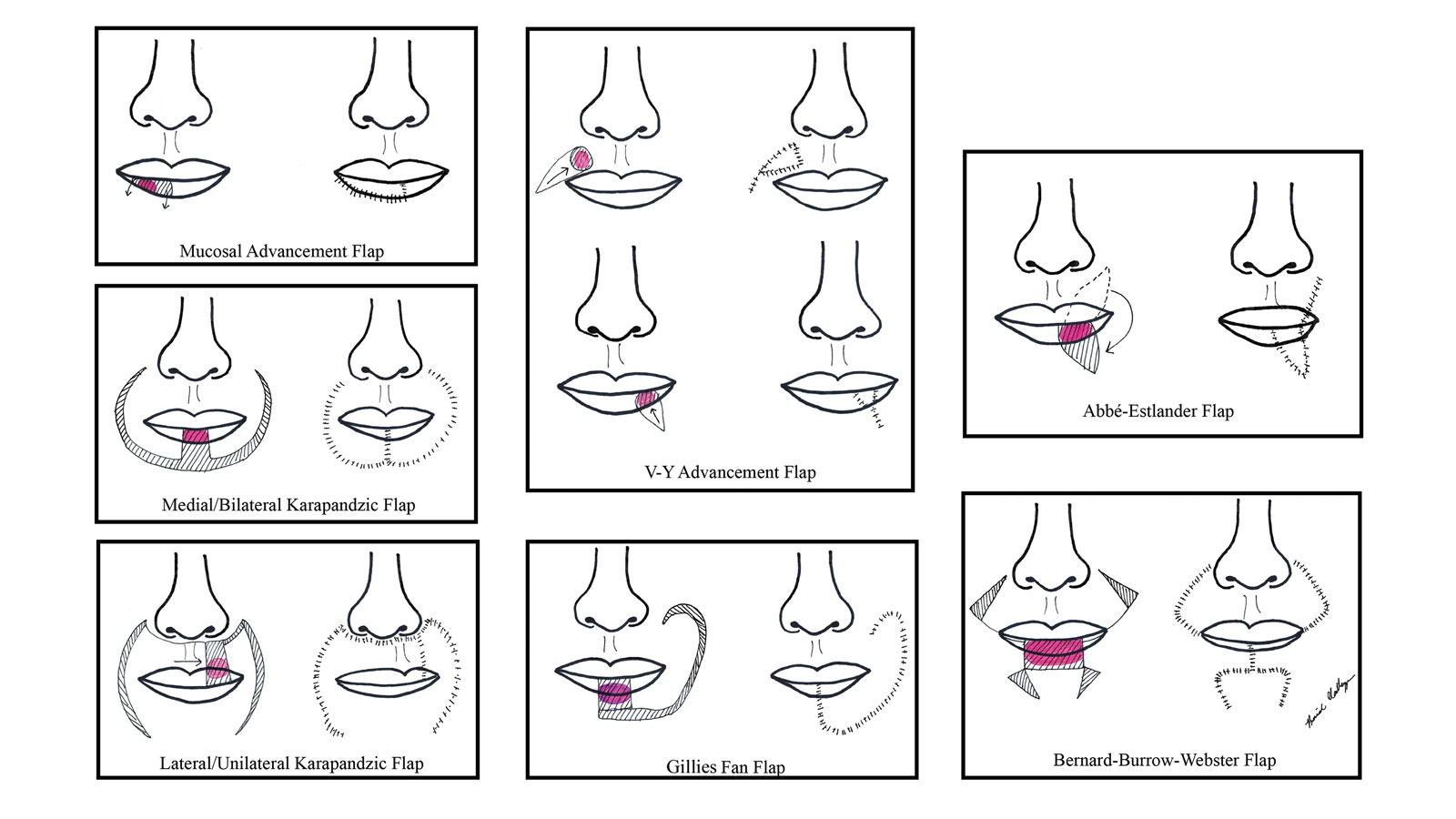

There are several local lip flap reconstruction options available, and choosing one is based on defect size and location. We provide a succinct review of the indications, risks, and benefits of commonly utilized flaps (Table), as well as artist renderings of all of the flaps (Figure).

Vermilion Flaps

Vermilion flaps are used to close partial-thickness defects of the vermilion border, an area that poses unique obstacles of repair with blending distant tissues to match the surroundings.8 Goldstein11 developed an adjacent ipsilateral vermilion flap utilizing an arterialized myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of vermilion defects. Later, this technique was modified by Sawada et al12 into a bilateral adjacent advancement flap for closure of central vermilion defects and may be preferred for defects 2 cm in size or larger. Bilateral flaps are smaller and therefore more viable than unilateral or larger flaps, allowing for a more aesthetic alignment of the vermilion border and preservation of muscle activity because muscle fibers are not cut. This technique also allows for more efficient stretching or medial advancement of the tissue while generating less tension on the distal flap portions. Burow triangles can be utilized if necessary for improved aesthetic outcome.1

Mucosal Advancement and Split Myomucosal Advancement Flap

The mucosal advancement technique can be considered for tumors that do not involve the adjacent cutaneous skin or the orbicularis oris muscle; thus, the reconstruction involves only the superficial vermilion area.7,13 Mucosal incisions are made at the gingivobuccal sulcus, and the mucosal flap is elevated off the orbicularis oris muscle and advanced into the defect.10 A plane of dissection is maintained while preserving the labial artery. Undermining effectively advances wet mucosa into the dry mucosal lip to create a neovermilion. However, the reconstructed lip often appears thinner and will possibly be a different shade compared to the adjacent native lip. These discrepancies become more evident with deeper defects.7

There is a risk for cosmetic distortion and scar contraction with advancing the entire mucosa. Eirís et al13 described a solution—a bilateral mucosal rotation flap in which the primary incision is made along the entire vermilion border and tissue is undermined to allow advancement of the mucosa. Because the wound closure tension lays across the entire lip, there is less risk for scar contraction, even if the flap movement is unequal on either side of the defect.13