‘You’ve been served’: What to do if you receive a subpoena

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Psychiatrists should not reveal what their patients say except to avert a threat to health or safety or to report abuse. So, how can psychiatrists be subpoenaed to provide information for a trial? If I receive a subpoena, how can I comply without violating patient privacy? If I have to go to court, can I “plead the Fifth”?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Physicians who are served with a subpoena feel upset for the reason Dr. S described: Complying with a subpoena seems to violate the obligation to protect patients’ privacy. But physicians can’t “plead the Fifth” under these circumstances, because the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only bars forcing someone to give self-incriminating testimony.1

If you receive a subpoena for information gleaned during patient care, you should not ignore it. Failing to respond might place you in contempt of court and subject you to a fine or even jail time. Yet simply complying could have legal and professional implications, too.

Often, a psychiatrist who receives a subpoena should seek an attorney’s advice on how to best respond. But understanding what subpoenas are and how they work might let you feel less anxious as you go through the process of responding. With this goal in mind, this article covers:

• what a subpoena is and isn’t

• 2 types of privacy obligations

• legal options

• avoiding potential embarrassment (Box).2

What is a subpoena?

All citizens have a legal obligation to furnish courts with the information needed to decide legal issues.3 Statutes and legal rules dictate how such material comes to court.

Issuing a subpoena (from the Latin sub poena, “under penalty”) is one way of obtaining information needed for a legal proceeding. A subpoena ad testificandum directs the recipient to appear at a legal proceeding and provide testimony. A subpoena duces tecum (“you shall bring with you”) directs the recipient to produce specific records or to appear at a legal proceeding with the records.

Usually, subpoenas are issued by attorneys or court clerks, not by judges. As such, they are not court orders. If you receive a subpoena, you should make a timely response of some sort. But, ultimately, you might not have to release the information. Although physicians have to follow the same rules as other citizens, courts recognize that doctors also have professional obligations to their patients.

Confidentiality: Your reason to hesitate

Receiving a subpoena doesn’t change your obligation to protect your patient’s confidentiality. From the law’s standpoint, patient confidentiality is a function of the rules that govern use of information in legal proceedings.

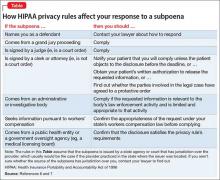

The Privacy Rule4 that arose from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 19965 provides guidance on acceptable responses to subpoenas by “covered entities,” which includes most physicians’ practices. HIPAA permits disclosure of the minimum amount of personal information needed to fulfill the demands of a subpoena. The Table6,7 explains HIPAA’s rules about specific responses to subpoenas, depending on their source.

Many states have patient privacy laws that are stricter than HIPAA rules. If you practice in one of those states, you have to follow the more stringent rule.8 For example, Ohio law does not let subpoenaed providers tender medical records for use in a grand jury proceeding without a release signed by the patient, although HIPAA would allow this (Table).6,7 Out of concern that “giving law enforcement unbridled access to medical records could discourage patients from seeking medical treatment,” Ohio protects patient records more than HIPAA does.9 New York State’s privilege rules also are stricter than HIPAA10 and contain specific provisions about releasing certain types of information (eg, HIV status11). State courts expect physicians to follow their laws about patient privacy and to consult attorneys to make sure that releasing information is done properly.12

Releasing information improperly could become grounds for legal action against you, even if you released the information in response to a subpoena. Legal action could take the form of a lawsuit for breach of confidentiality, a HIPAA-based complaint, a complaint to the state medical board, or all 3 of these.

Must you turn over information?

Before you testify or turn over documents, you need to verify that the legal and ethical requirements for the disclosure are met—as you would for any release of patient information. You can do this by obtaining your patient’s formal, written consent for the disclosure. Before you accept the patient’s agreement, however, you might—and in most cases should— consider discussing how the disclosure could affect the patient’s well-being or your treatment relationship.