Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction: Current Philosophy in 2016

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary static restraint to valgus stress at the elbow. Since Jobe pioneered reconstruction in 1974, thousands of throwers have undergone UCL reconstruction, and good results have been achieved. The high-profile nature of the elite pitcher has brought this technique into the spotlight, and extensive research has been performed with new techniques emerging. The standard reconstruction, modified only slightly since Jobe’s original description, remains the gold standard for treatment of UCL insufficiency. Throwers are able to return to the same or even higher levels of competition in the majority of cases. In this article, we present our standard technique and results and discuss emerging techniques for treatment of UCL injuries.

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary restraint to valgus stress between 20° and 125° of motion.1-5 Overhead athletes, most commonly baseball pitchers, are at risk of developing UCL insufficiency, and dysfunction presents as pain with loss of velocity and control. Some injuries may present acutely while throwing, but many patients, when questioned, report a preceding period of either pain or loss of velocity and control.

Authors have documented a significant rise in elbow injuries in young athletes, especially pitchers.6 Extended seasons, higher pitch counts, year-round pitching, pitching while fatigued, and pitching for multiple teams are risk factors for elbow injuries.7 Pitchers in the southern United States are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction than those from the northern states.8 Pitchers who also play catcher are at a higher risk due to more total throws than those who pitch and play other positions or pitch only. Throwers with higher velocity are more likely to pitch in showcases, pitch for multiple teams, and pitch with pain and fatigue, and these are all risk factors.6 Also, in one study of youth baseball injuries, individuals in the injured group were found to be taller and heavier than those in the uninjured group.6 Pitch counts, rest from pitching during the off-season, adequate rest, and ensuring pain-free pitching can lessen the risk of injury.6 As expected with the rise in throwing injuries, the rise in medial elbow procedures has risen.9

While throwing, stress across the medial elbow has been measured to be nearly 300 N. A maximum varus force during pitching was measured to be 64 N-m at 95° ± 14°.10 Morrey and An4 determined that the UCL generated 54% of the varus force at 90° of flexion. During active pitching, this value is likely reduced due to simultaneous muscle contraction, but if one assumes the UCL bears 54% of the maximal load, the UCL must be able to withstand 34 N-m. The UCL can withstand a maximum valgus torque between 22.7 and 34 N-m11-13; therefore, during pitching, the UCL is at or above its failure load. After thousands of cycles over many years, one can imagine how the UCL might be injured.

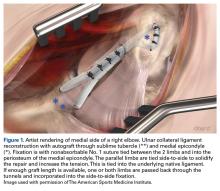

Multiple techniques have been proposed in the surgical treatment of UCL injuries. Jobe14 pioneered UCL reconstruction in 1974 in Tommy John, a Major League Baseball pitcher. John returned to pitch successfully, and both the UCL and the reconstruction are commonly called by his name. Jobe14 reported his technique in 1986, and it has remained, with a few modifications, the primary method for reconstruction of the UCL (Figure 1).

Evaluation

A standard evaluation with physical examination and imaging is completed in all throwers with elbow pain. In our prior study,16 we found that 100% of patients experienced pain during athletic activity and that 96% of throwers complained of pain during late cocking and acceleration phases of the throwing motion. Nearly half reported an acute onset of pain, while 53% were unable to identify a single inciting event. Seventy-five percent of the acute injuries were during competition. Delayed diagnosis was very common, with an average time to diagnosis after onset of symptoms of 6.4 months. Neurologic symptoms were seen in 23% of athletes, most of which were ulnar nerve paresthesias during throwing.16

Physical examination includes inspection for swelling, hand intrinsic atrophy, neurovascular examination, range of motion, shoulder examination, and elbow stress examination. Range of motion at presentation averaged 5° to 135° with 85° of supination and pronation.16 All patients need neurologic evaluation for ulnar nerve dysfunction. Tinel test of the cubital tunnel was positive in 21%.16 Significant ulnar nerve dysfunction, including hand weakness, is much less common but must be well examined and documented. The shoulder must also be evaluated for loss of rotation, which can lead to increased stress on the elbow. An evaluation of mechanics may point out flaws in technique, which may be contributing to elbow stress. The UCL stress examination includes static stress at 30° of flexion, the milking test at 90°, and the moving valgus stress test. The presence of pain directly over the UCL or laxity compared to the uninvolved side is suggestive of UCL injury.

Radiographic evaluation is completed in all patients with concern for UCL injury. Standard x-rays of the elbow, including anteroposterior, medial, and lateral obliques, axial olecranon, and lateral views, are obtained to evaluate bony abnormalities. Fifty-seven percent of our series showed some abnormality, most commonly olecranon osteophyte formation or ectopic calcification within the UCL substance. Stress radiography rarely changed the treatment course and is somewhat difficult to interpret because of the reports documenting normal increased medial elbow opening in the dominant arm of throwing athletes.21 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is obtained very commonly in this patient population, and intra-articular contrast is crucial. Partial, undersurface tears are common, and a contrasted study better demonstrates undersurface tears or avulsions. The T-sign as described by Timmerman and colleagues22 using computed tomography (CT) arthrography shows partial undersurface detachment, which can be difficult to see without intra-articular contrast.22 This finding is very well visualized on MRI arthrogram as well (Figure 3).