Thinking Outside the Checkbox

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

A 34-year-old, previously healthy Japanese man developed a dry cough. He did not have dyspnea, nasal discharge, sore throat, facial pain, nasal congestion, or postnasal drip. His symptoms persisted despite several courses of antibiotics (from different physicians), including clarithromycin, minocycline, and levofloxacin. A chest x-ray after 2 months of symptoms and a noncontrast chest computed tomography (CT) after 4 months of symptoms were normal, and bacterial and mycobacterial sputum cultures were sterile. Treatment with salmeterol and fluticasone was ineffective.

The persistence of a cough for longer than 8 weeks constitutes chronic cough. The initial negative review of systems argues against several of the usual etiologies. The lack of nasal discharge, sore throat, facial pain, nasal congestion, and postnasal drip lessens the probability of upper airway cough syndrome. The absence of dyspnea decreases the likelihood of congestive heart failure, asthma, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Additional history should include whether the patient has orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or a reduced exercise tolerance.

The persistence of symptoms despite multiple courses of antibiotics suggests that the process is inflammatory but not infectious, that the infection is not susceptible to the selected antibiotics, that the antibiotics cannot penetrate the site of infection, or that the ongoing symptoms are related to the antibiotics themselves. Pathogens that may cause chronic cough for months include mycobacteria, fungi (eg, Aspergillus , endemic mycoses), and parasites (eg, Strongyloides , Paragonimus ). Even when appropriately treated, many infections may result in a prolonged cough (eg, pertussis). The fluoroquinolone and macrolide exposure may have suppressed the mycobacterial cultures. The lack of response to salmeterol and fluticasone lessens the probability of asthma.

After 4 months of symptoms, his cough worsened, and he developed dysphagia and odynophagia, particularly when he initiated swallowing. He experienced daily fevers with temperatures between 38.0°C and 38.5°C. A repeat chest x-ray was normal. His white blood cell count was 14,200 per μL, and the C-reactive protein (CRP) was 12.91 mg/dL (normal <0.24 mg/dL). His symptoms did not improve with additional courses of clarithromycin, levofloxacin, or moxifloxacin. After 5 months of symptoms, he was referred to the internal medicine clinic of a teaching hospital in Japan.

The patient’s fevers, leukocytosis, and elevated CRP signal an inflammatory process, but whether it is infectious or not remains uncertain. The normal repeat chest x-ray lessens the likelihood of a pulmonary infection. Difficulty with initiating a swallow characterizes oropharyngeal dysphagia which features coughing or choking with oral intake and is typically caused by neuromuscular conditions like stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or myasthenia gravis. The coexistence of oropharyngeal dysphagia and odynophagia may indicate pharyngitis, a retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal abscess, or oropharyngeal cancer.

Esophageal dysphagia occurs several seconds following swallow initiation and may arise with mucosal, smooth muscle, or neuromuscular diseases of the esophagus. Concomitant dysphagia and odynophagia may indicate esophageal spasm or esophagitis. Causes of esophagitis include infection (eg, candidiasis, herpes simplex virus [HSV], cytomegalovirus [CMV], or human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), infiltration (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), or irritation (eg, from medication, caustic ingestion, or gastroesophageal reflux). He is at risk for esophageal candidiasis following multiple courses of antibiotics. Esophageal dysphagia occurring with liquids and solids may indicate disordered motility, as opposed to dysphagia with solids alone, which may signal endoluminal obstruction.

At his outpatient evaluation, he denied headache, vision changes, chest pain, hemoptysis, palpitations, abdominal pain, dysuria, musculoskeletal symptoms, anorexia, or symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. He did not have chills, rigors, or night sweats, but he had lost 3.4 kg in 5 months. He had not traveled within or outside of Japan in many years and was not involved in outdoor activities. He was engaged to and monogamous with his female partner of 5 years. He smoked 10 cigarettes per day for 14 years but stopped smoking during the last 2 months on account of his symptoms. He drank 6 beers per month and worked as a researcher at a chemical company but did not have any inhalational exposures.

His weight loss could be from reduced caloric intake due to dysphagia and odynophagia or may reflect an energy deficit related to chronic illness and inflammatory state. His smoking history increases his risk of bronchopulmonary infection and malignancy. Bronchogenic carcinoma may present with chronic cough, fevers, weight loss, or dysphagia from external compression by lymphadenopathy or mediastinal disease; however, his young age and recent chest CT results make lung cancer unlikely.

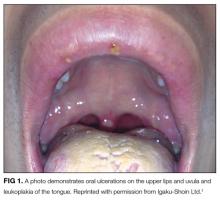

The white coating on his tongue could reflect oral leukoplakia, a reactive and potentially precancerous process that typically manifests as patches or plaques on oral mucosa. It can be distinguished from candidiasis, which scrapes off using a tongue blade. The extensive tongue coating is consistent with oral candidiasis. Potential predispositions include inhaled corticosteroids, antibiotic exposure, and/or an undiagnosed immunodeficiency syndrome (eg, HIV).