Supporting the Needs of Stroke Caregivers Across the Care Continuum

From the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Wilmington, NC (Dr. Lutz), and the Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center, Kaiser Permanente, Vallejo, CA (Ms. Camicia).

Abstract

- Objectives: To describe issues faced by stroke family caregivers, discuss evidence-based interventions to improve caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians caring for stroke survivors and their family caregivers.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Caregiver health is linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of functional recovery; the more severe the level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health. Inadequate caregiver preparation contributes to poorer outcomes. Caregivers describe many unmet needs including skills training; communicating with providers; resource identification and activation; finances; respite; and emotional support. Caregivers need to be assessed for gaps in preparation to provide care. Interventions are recommended that combine skill-building and psycho-educational strategies; are tailored to individual caregiver needs; are face-to-face when feasible; and include 5 to 9 sessions. Family counseling may also be indicated. Intermittent assessment of caregiving outcomes should be conducted so that changing needs can be addressed.

- Conclusions: Stroke caregiving affects the caregiver’s physical, mental, and emotional health, and these effects are sustained over time. Poorly prepared caregivers are more likely to experience negative outcomes and their needs are high during the transition from inpatient care to home. Ongoing support is also important, especially for caregivers who are caring for a stroke survivor with moderate to severe functional limitations. In order to better address unmet needs of stroke caregivers, intermittent assessments should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to their changing needs over time.

Key words: stroke; family caregivers; care transitions; patient-centered care.

Stroke is a leading cause of major disability in the United States [1] and around the world [2]. Of the estimated 6.6 million stroke survivors living in the US, more than 4.5 million have some level of disability following stroke [1]. In 2009, more than 970,000 persons were hospitalized with stroke in the US with an average length of stay of 5.3 days [3]. Approximately 44% of stroke survivors are discharged home directly from acute care without post-acute care [4]. Only about 25% of stroke survivors receive care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities [4] even though the American Heart Association (AHA) stroke rehabilitation guidelines recommend this level of care for qualified patients [5]. Regardless of the care trajectory, when stroke survivors return home they frequently require assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL/IADL), usually provided by family members who often feel unprepared and overwhelmed by the demands and responsibilities of this caregiving role.

The deleterious effects of caregiving have been identified as a major public health concern [6]. A robust body of literature has established that caregivers are often adversely affected by the demands of their caregiving role. However, much of this literature focuses on caregivers for persons with dementia. Needs of stroke caregivers are categorically different from caregivers of persons with dementia in that stroke is an unpredictable, life-disrupting, crisis event that occurs suddenly leaving family members with insufficient time to prepare for the new roles and caregiving responsibilities. The patient typically transitions from being cared for by multiple providers in an acute care, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or skilled nursing facility (SNF)—24 hours a day, 7 days a week—to relying fully on one person (most often a spouse or adult child) who may not be ready to handle the overwhelming demands and constant vigilance required for adequate care at home. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the damaging health effects of caregiving. Caregivers describe feeling isolated, abandoned, and alone [7–9], and what frequently follows is a predictable trajectory of depression and deteriorating health and well-being [7,10–13]. The purpose of this article is to describe difficulties and issues faced by family members who are caring for a loved one following stroke, discuss evidence-based interventions designed to improve stroke caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians who care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers post-stroke.

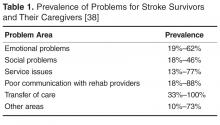

Difficulties and Issues Faced by Caregivers

With an aging population and increasing incidence of stroke, it is imperative that we identify and address the ongoing needs of stroke survivors and their family caregivers in the post-stroke recovery period. Multiple studies acknowledge that stroke is a life-changing event for patients and their family members [9,14] that often results in overwhelming feelings of uncertainty, fear [15], grief, and loss [9]. Stroke also can have long-term effects on the health of stroke survivors and their family caregivers. Studies have identified the effects of caregiving on the health of caregivers and subsequent links between stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes over time [12,16,17]; the ongoing needs of stroke caregivers post-discharge [18,19]; and the importance of assessing caregiver preparedness and subsequent caregiving outcomes [5,20].

Effects of Caregiving on the Health of Caregivers and Stroke Survivors

Research on stroke caregiving consistently indicates that caregiver health is inextricably linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of physical, cognitive, psychological, and emotional recovery. The more severe the patient’s level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health outcomes [21]. Studies also indicate that certain caregiver characteristics, such as being female or having lower educational level, pre-existing health conditions [7,22,23], poor family functioning, lack of social support [22,24], or lack of preparation [25], are all risk factors for poorer caregiver outcomes.

Stroke family caregivers often experience overwhelming physical and emotional strain, depressive symptoms, sleep deprivation, decline in physical and mental health, reduced quality of life, and increased isolation [7,10,11,14,26,27]. Perceived burden has been positively associated with caregiver depressive symptoms [12,14,28,29]. Depressive symptoms in caregivers, with a reported incidence of 14% [30] to 33% [31], may persist for several years post-stroke. In a study of the long-term effects of caregiving with 235 stroke caregivers when compared with non-caregivers, researchers found that caregivers had more depressive symptoms and poorer life satisfaction and mental health quality of life at 9 months post-stroke, and many of these differences continued for 3 years post-discharge [23].

Lower stroke survivor functioning and higher depressive symptoms are correlated with higher caregiver depressive symptoms and burden, and poorer coping skills and mental health [12,21]. A review of stroke caregiving literature by van Heugten et al [32] indicated that long-term caregiver functioning was influenced by stroke survivor physical and cognitive functioning and behavioral issues; caregiver psychological and emotional health; quality of family relationships; social support; and caregiver demographics. Caregivers of stroke survivors with aphasia may have more difficulties providing care, increased burden and strain, higher depressive symptoms, and other negative stroke-related outcomes [33].

Gaugler [34] conducted a systematic review of 117 studies and reported that caring for stroke survivors who were older, in poorer health, and had greater stroke severity increased the likelihood of poorer emotional and psychological family caregiver outcomes. Caregivers who had “negative problem orientation and less social support” were more likely to have depressive symptoms and poorer self-rated health at 1-year post-stroke. One of the best predictors of caregiver stress and poor health in the first year post-stroke was lack of caregiver preparation [25,34].

Research also suggests that stroke survivor outcomes are influenced by the ability of the family caregiver to provide emotional and instrumental support as well as assistance with BADL/IADL [6,35]. As the caregiver’s health decreases, the stroke survivor’s health and recovery will also likely suffer and ultimately may result in re-hospitalization or nursing home placement. For example, Perrin et al found a consistent reciprocal relationship between caregiver health and stroke survivor functioning, such that the quality of caregiving may be affected by caregiver burden and depressive symptoms, which in turn can impair the functional, psychological, and emotional recovery of the stroke survivor [21]. Studies have also linked poorer caregiver well-being to increased depressive symptoms in stroke survivors [36,37].