NetWorks: Uranium mining, hyperoxia, palliative care education, OSA impact

Health effects of uranium mining

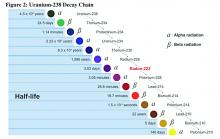

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.