Managing risks of TNF inhibitors: An update for the internist

ABSTRACTTumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have many beneficial effects, but they also pose infrequent but significant risks, including serious infection and malignancy. These risks can be minimized by judicious patient selection, appropriate screening, careful monitoring during treatment, and close communication between primary care physicians and subspecialists.

KEY POINTS

- Over the past 10 years, TNF inhibitors have substantially altered the management of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

- Safety concerns include risks of infection, reactivation of latent infection (eg, fungal infection, granulomatous infection), malignancy, and autoimmune and neurologic effects.

- Before treating, take a complete history, including exposure to latent infections and geographic considerations, and bring patients’ immunizations up to date.

- Regular clinical and laboratory monitoring during treatment helps optimize therapy and minimize the risk of adverse effects.

- Physicians must be aware of atypical presentations of infection and understand how their treatment may differ in patients on biologic therapy.

Biologic agents such as those that block tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha have revolutionized the treatment of autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, dramatically improving disease control and quality of life. In addition, they have made true disease remission possible in some cases.

However, as with any new therapy, a variety of side effects must be considered.

WHAT ARE BIOLOGIC AGENTS?

Biologic agents are genetically engineered drugs manufactured or synthesized in vitro from molecules such as proteins, genes, and antibodies present in living organisms. By targeting specific molecular components of the inflammatory cascade, including cytokines, these drugs alter certain aspects of the body’s inflammatory response in autoimmune diseases. Because TNF inhibitors are the most widely used biologic agents in the United States, this review will focus on them.

TNF INHIBITORS

TNF inhibitors suppress the inflammatory cascade by inactivating TNF alpha, a cytokine that promotes inflammation in the intestine, synovial tissue, and other sites.1,2

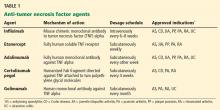

Several TNF inhibitors are available. Etanercept and infliximab were the first two to receive US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, and they are extensively used. Etanercept, a soluble TNF receptor given subcutaneously, was approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis in 1998. Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody (75% human and 25% mouse protein sequence) given intravenously, received FDA approval for treating Crohn disease in 1998 and for rheumatoid arthritis in 1999. Other anti-TNF agents with varying properties are also available.

Table 1 lists anti-TNF agents approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. These are chronic, relapsing diseases that significantly and dramatically reduce quality of life, especially when they are poorly controlled.3,4 Untreated disease has been associated with malignancy, infection, pregnancy loss, and malnutrition.5–8 TNF inhibitors are aimed at patients who have moderate to severe disease or for whom previous treatments have failed, to help them achieve and maintain steroid-free remission. However, use of these agents is tempered by the risk of potentially serious side effects.

Special thought should also be given to the direct costs of the drugs (up to $30,000 per year, not counting the cost of their administration) and to the indirect costs such as time away from work to receive treatment. These are major considerations in some cases, and patients should be selected carefully for treatment with these drugs.

BEFORE STARTING THERAPY

Before starting anti-TNF therapy, several steps can reduce the risk of serious adverse events.

Take a focused history

The clinical history should include inquiries about previous bacterial, fungal, and tuberculosis infections or exposure; diabetes; and other immunocompromised states that increase the risk of acquiring potentially life-threatening infections.

Details of particular geographic areas of residence, occupational exposures, and social history should be sought. These include history of incarceration (which may put patients at risk of tuberculosis) and residence in the Ohio River valley or in the southwestern or midwestern United States (which may increase the risk of histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and other fungal infections).

Bring vaccinations up to date

Age-appropriate vaccinations should be discussed and given, ideally before starting therapy. These include influenza vaccine every year and tetanus boosters every 10 years for all and, as appropriate, varicella, human papillomavirus, and pneumococcal vaccinations. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend an additional dose of the pneumococcal vaccine if more than 5 years have elapsed since the first one, and many clinicians opt to give it every 5 years.

In general, live-attenuated vaccines, including the intranasal influenza vaccine, are contraindicated in patients taking biologic agents.9 For patients at high risk of exposure or infection, it may be reasonable to hold the biologic agent for a period of time, vaccinate, and resume the biologic agent a month later.

Recent data suggest that the varicella zoster vaccine may be safely given to older patients with immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease taking biologic agents.10 New guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology recommend age-appropriate vaccines for rheumatoid arthritis patients age 60 and older before biologic treatments are started. Case-by-case discussion with the subspecialist and the patient is recommended.

Screen for chronic infections

Tuberculosis screening with a purified protein derivative test or an interferon-gamma-release (Quantiferon) assay followed by chest radiography in patients with a positive test is mandatory before giving a TNF inhibitor.

Hepatitis B virus status should be determined before starting anti-TNF therapy.11

Hepatitis B vaccination has been recommended for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, but no clear recommendation exists for patients with rheumatic disease. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease tend to have low rates of response to hepatitis B vaccination12,13; possible reasons include their lack of an appropriate innate immune response to infectious agents, malnutrition, surgery, older age, and immunosuppressive drugs.14 An accelerated vaccination protocol with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Energix-B) in a double dose at 0, 1, and 2 months has been shown to improve response rates.15

Whenever possible, it may be better to vaccinate patients before starting immunosuppressive therapy, and to check postvaccination titers to ensure adequate response.