Accountable Care Organizations: Early Results and Future Challenges

From the Harvard Medical School and the Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

In recent years, the growth of health care spending has climbed to the top of the domestic policy agenda. Medicare spending growth is now recognized as the biggest driver of the federal debt [1,2].Medicaid spending growth puts similar pressure on states. In the private sector, employee health care costs increasingly weigh on company balance sheets, affecting business operations and employee wages. All the while, individuals and families face insurance premium growth that far outpaces real income growth.

Out of this recent history emerged a broad recognition that health care spending growth is unsustainable at current rates. If Medicare spending continues to exceed gross domestic product (GDP) by 2.5 percentage points per year—the traditional gap over the past 4 decades—a greater than 160% increase in individual income taxes would be needed to pay for it [3].Even if the gap was 1 percentage point, the increase in income taxes needed would still be over 70%, with consequent contraction in GDP of 3% to 16% by 2015 [4,5].Other consequences, such as significant cuts in Medicare benefits or shifting of costs onto patients, are equally undesirable [6,7].

Policy options for slowing health care spending are varied. Some focus on changing the provider’s incentives, while others focus on changing the patient’s incentives. Some are based on federal solutions [8],while others are based on market solutions [9].In the current policy landscape, payment reform for physicians and hospitals has emerged as a leading candidate for addressing health care spending. Public and private payers are increasingly changing the way that providers are paid, moving away from fee-for-service towards bundled or global payments for populations of patients. Physicians and hospitals are in turn forming integrated provider organizations to take on these new payment systems. The pace of this change has been growing.

Key Features of the ACO Concept

An accountable care organization (ACO) is a group of providers—that can include both physicians and hospitals—that accepts joint responsibility for health care spending and quality for a defined population of patients. The ACO concept can be considered an extension of the staff-model health maintenance organization (HMO) [13,14].It also shares features with the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model in its focus on a robust primary care nexus that serves to coordinate a patient’s care [15,16].Three key characteristics are embedded in this definition.

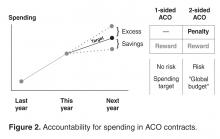

The first is joint accountability. In an ACO contract, incentives for providers are agreed upon at the organizational level. Physicians and hospitals bear the financial risks and rewards of the ACO contract together. Shared savings, quality bonuses, and other incentives are determined by how the organization performs as a whole rather than any individual physician, practice, or hospital. In this way, physicians across specialties and care settings are incentivized to approach patient care collectively and coordinate care more effectively.

Third, an ACO is responsible for the care of a population of people. Each year, spending and quality are measured for the population attributed, or assigned, to the ACO. Attribution of patients to organizations can take place in two ways. It can be prospective, meaning that before the start of a contract year, the ACO knows exactly the patients whose spending and quality it is responsible for. This is typically more feasible in commercial ACO contracts, especially in the HMO population, where patients designate a primary care physician at the beginning of the year. Otherwise, attribution is typically retrospective, such as in the Medicare ACO programs, where beneficiaries are assigned to organizations at the end of a contract year based on the organization which accounted for the plurality of a patient’s medical spending or primary care spending.