Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A complex disease

ABSTRACT

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex cardiovascular disease with wide phenotypic variations. Despite significant advances in imaging and genetic testing, more information is needed about the roles and implications of these resources in clinical practice. Patients with suspected or established HCM should be evaluated at an expert referral center to allow for the best multidisciplinary care. Research is needed to better predict the risk of sudden cardiac death in those judged to be at low risk by current risk-stratification methods.

KEY POINTS

- Obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract is a key pathophysiologic mechanism in HCM.

- Because most of the genetic variants that contribute to HCM are autosomal dominant, genetic counseling and testing are suggested for patients and their first-degree relatives.

- Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line imaging test, followed by magnetic resonance imaging.

- Beta-blockers are the first-line drugs for treating symptoms of HCM.

- An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator can be considered for patients at risk of sudden cardiac death.

- When medical therapy fails or is not tolerated in patients with severe symptoms of obstructive HCM, surgery to reduce the size of the ventricular septum can be considered. Alcohol septal ablation is an alternative.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex disease. Most people who carry the mutations that cause it are never affected at any point in their life, but some are affected at a young age. And in rare but tragic cases, some die suddenly while competing in sports. With such a wide range of phenotypic expressions, a single therapy does not fit all.

HCM is more common than once thought. Since the discovery of its genetic predisposition in 1960, it has come to be recognized as the most common heritable cardiovascular disease.1 Although earlier epidemiologic studies had estimated a prevalence of 1 in 500 (0.2%) of the general population, genetic testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now show that up to 1 in 200 (0.5%) of all people may be affected.1,2 Its prevalence is significant in all ethnic groups.

This review outlines our expanding knowledge of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of HCM.

A PLETHORA OF MUTATIONS IN CARDIAC SARCOMERIC GENES

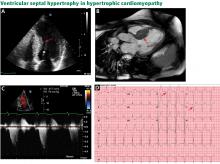

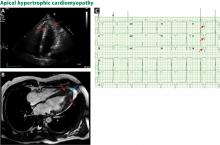

The genetic differences within HCM result in varying degrees and locations of left ventricular hypertrophy. Any segment of the ventricle can be involved, although HCM is classically asymmetric and mainly involves the septum (Figure 1). A variant form of HCM involves the apex of the heart (Figure 2).

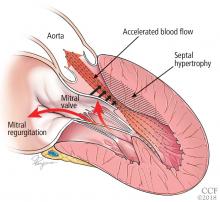

LEFT VENTRICULAR OUTFLOW TRACT OBSTRUCTION

Only in the last decade has the significance of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM been truly appreciated. The degree of obstruction in HCM is dynamic, as opposed to the fixed obstruction in patients with aortic stenosis or congenital subvalvular membranes. Therefore, in HCM, exercise or drugs (eg, dobutamine) that increase cardiac contractility increase the obstruction, as do maneuvers or drugs (the Valsalva maneuver, nitrates) that reduce filling of the left ventricle.

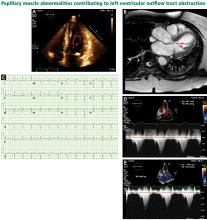

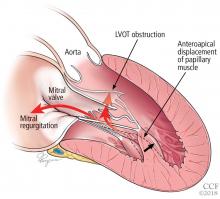

A less common source of dynamic obstruction is the papillary muscles (Figure 4). Hypertrophy of the papillary muscles can result in obstruction by these muscles themselves, which is visible on echocardiography. Anatomic variations include anteroapical displacement or bifid papillary muscles, and these variants can be associated with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, even with no evidence of septal thickening (Figure 5).7,8 Recognizing this patient subset has important implications for management, as discussed below.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The clinical presentation varies

Even if patients harbor the same genetic variant, the clinical presentation can differ widely. Although the most feared presentation is sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes, most patients have no symptoms and can anticipate a normal life expectancy. The annual incidence of sudden cardiac death in all HCM patients is estimated at less than 1%.10 Sudden cardiac death in HCM patients is most often due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias and most often occurs in asymptomatic patients under age 35.

Physical findings are nonspecific

It can be difficult to distinguish the murmur of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM from a murmur related to aortic stenosis by auscultation alone. The simplest clinical method for telling them apart involves the Valsalva maneuver: bearing down creates a positive intrathoracic pressure and limits venous return, thus decreasing intracardiac filling pressure. This in turn results in less separation between the mitral valve and the ventricular septum in HCM, which increases obstruction and therefore makes the murmur louder. In contrast, in patients with fixed obstruction due to aortic stenosis, the murmur will decrease in intensity owing to the reduced flow associated with reduced preload.