Early Parkinsonism: Distinguishing Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease from Other Syndromes

From the VA Medical Center (Dr. Lehosit) and the Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Center, Virginia Commonwealth University (Dr. Cloud), Richmond, VA.

Abstract

- Objective: To provide an overview of the importance and challenges of accurate diagnosis of early idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and practical guidelines for clinicians.

- Methods: Review of the relevant literature.

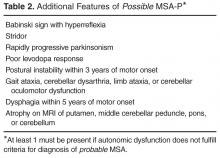

- Results: Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease is a common neurodegenerative disorder causing a wide spectrum of motor and nonmotor symptoms. The cardinal motor features include resting tremors, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. The diagnosis is clinical, and ancillary laboratory or radiology tests are unnecessary in typical cases. Despite the use of validated diagnostic criteria, misdiagnosis is common, especially early in the disease process. This is largely due to the phenotypic heterogeneity in the idiopathic Parkinson’s disease population as well phenotypic overlapping with other diseases. The diseases most commonly confused with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease are the Parkinson-plus syndromes (dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration), vascular parkinsonism, drug-induced parkinsonism, dopa responsive dystonia, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and essential tremor. Since the diagnosis of these other diseases is also clinical, familiarity with their typical presentations and most current diagnostic criteria is helpful. Brain MRI can be helpful in diagnosing some of the diseases, though brain imaging is most commonly unremarkable in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. DaTscan has an FDA indication to assist in the evaluation of adults with parkinsonian syndromes. It should not be used in typical cases but can be a useful adjunct to other diagnostic evaluations in atypical cases.

- Conclusion: Despite the challenges involved, accurate and early diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease is essential for optimal patient education, counseling, and treatment.

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD) is a common neurodenerative disease, affecting 1% of the population over the age of 65 [1]. A definitive diagnosis requires the postmortem findings of degeneration of the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of Lewy bodies (insoluble cytoplasmic inclusions composed of aggregated alpha-synuclein). In the later stages of the disease, a correct clinical diagnosis is made in more than 90% of patients [2]. Early on, however, clinical diagnosis is less reliable. For clinicians, distinguishing early IPD from other parkinsonian syndromes can be extraordinarily challenging because these conditions, especially in the earliest stages, present with highly variable yet overlapping phenotypes [3]. Furthermore, most of the diseases in the differential diagnosis, including IPD itself, are clinical diagnoses made on the basis of history and examination without the benefit of laboratory or radiology data. A high level of clinical acumen is therefore required for early and accurate diagnosis. Recent clinical trials in which subspecialists performed stringent diagnostic assessments to identify subjects with clinically diagnosed IPD later found that some subjects had normal functional dopamine imaging, suggesting that they probably did not have IPD [4,5]. These trials served to highlight the possibility of misdiagnosis, even in the hands of highly trained subspecialists. Early and accurate diagnosis is of paramount importance for many reasons. First, treatment approaches differ significantly across many of these diseases. Second, as neuroprotective interventions that are currently under investigation become available, long-term outcomes may significantly improve with earlier diagnosis and intervention. Third, some of these diseases are prognostically very different from one another, so accurate diagnosis enables better counseling and setting realistic expectations for progression.

This review will discuss the most common presenting signs and symptoms of early IPD, present the most widely used diagnostic criteria, and introduce the ancillary laboratory and imaging tests that may be helpful in distinguishing it from its mimics. The diseases most commonly confused with early IPD will also be discussed with an emphasis on the ways they most commonly differ from IPD. We will begin our discussion with the presenting signs and symptoms of IPD.

Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease

IPD typically has a subtle and insidious onset with characteristic features developing over months to years. IPD most often presents in patients after age 60, and age is the most consistent risk factor for developing IPD; however, approximately 5% of IPD cases begin before age 40 years. These young-onset cases are likely to be caused by genetic mutations [6]. The widely recognized cardinal motor features of IPD include asymmetric resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability [7]. Asymmetry is a key feature, as symptoms typically start on one side and remain more prominent on that side as the disease progresses. In fact, lack of asymmetry suggests an alternative diagnosis. Of the cardinal motor features, tremor is most often reported by patients as the first symptom [8]. However, IPD can alternately present with various other motor or even nonmotor complaints that will be discussed later.

Motor Features

Resting tremor is the most common presenting sign/symptom of early IPD, found in approximately 70% of patients [8]. The tremor typically is asymmetric and intermittent at onset, often starting in one hand. It is sometimes, though not necessarily, described as a “pill-rolling” rhythmic movement of the thumb and first finger while the hand is at rest. Patients will usually report a worsening of tremor with stress, anxiety, and increased fatigue. The tremor does not persist during sleep and diminishes with voluntary activity of the affected limb(s). By having the patient perform mentally challenging tasks (such as counting backwards) or motor movements of other body parts (such as finger tapping with the other hand or walking), the examiner may notice an increase in tremor amplitude [11]. There may also be a resting tremor of the lip or lower jaw, but true head tremor suggests an alternate diagnosis such as essential tremor [12]. Postural tremor can co-exist with resting tremor in IPD, which often leads to diagnostic confusion, especially when the postural tremor is more prominent than the resting tremor. In this scenario, the distinction between IPD and essential tremor (discussed later) can become more difficult.

Rigidity is characterized as the presence of increased resistance to passive stretch throughout the range of motion [13]. “Lead pipe” rigidity remains sustained throughout the motion of the joint, while “cogwheel” rigidity is intermittent through the movement. The examiner must take care to distinguish between true rigidity and other forms of increased tone such as spasticity (a velocity dependent increase in tone) and paratonia (a resistance to passive motion created by the patient). Subtle rigidity can be enhanced in a limb by having the patient perform a voluntary movement of the contralateral limb [14]. Rigidity in early IPD is also asymmetric and most commonly found in the upper extremities, but it can be seen in the neck and lower extremities as well. Patients may initially complain of shoulder pain and stiffness that is diagnosed as rotator cuff disease or arthritis, when this pain is actually due to rigidity from Parkinson’s disease [15]. Severe axial rigidity out of proportion to appendicular rigidity, however, should suggest an alternate diagnosis in the early stages of the disease (such as progressive supranuclear palsy which is further discussed below).

Bradykinesia refers to decreased amplitude and speed of voluntary motor movements. This sign can be found throughout the body in the form of hypometric saccades, decreased blink rate, decreased facial expressions (“masked facies”) and softening of speech (hypophonia) [16]. Patients may initially report a general slowing down of movements as well as difficulty with handwriting due to their writing becoming smaller (micrographia) [17]. Bradykinesia is evaluated by testing the speed, amplitude, and rhythmicity of voluntary movements such as repetitive tapping of the thumb and first finger together, alternation of supination and pronation of the forearm and hand, opening and closing the hand and tapping the foot rhythmically on the floor. The examiner should also evaluate for generalized bradykinesia by viewing the patient rise from a seated to standing position as well as observing the patient’s normal speed of ambulation and speed and symmetry of arm swing.

Gait disturbance and postural instability can sometimes be found in early IPD; however, significant impairment of postural reflexes, gait impairment and early falls may point to a diagnosis other than IPD. Early IPD postural changes include mild flexion of the neck or trunk that may be accompanied by a slight leaning to one side. On examination of natural gait, the patient may exhibit asymmetrically reduced arm swing, slowing of gait and turning, shortened stride length and intermittent shuffling of the feet. With disease progression, all of these become more severe and there may be festination of gait (“hurried” gate with increased cadence and difficulty stopping). This can lead to instability and falls as the patient’s center of balance is displaced forward. Freezing of gait can also develop, but is rarely found in early IPD [18]. Postural stability is evaluated by the “pull test” where the patient is asked to stand in a comfortable stance with eyes open and feet apart and instructed to resist falling backwards when pulled by the examiner. The patient is allowed to take one step backwards with either foot if necessary to prevent falling. This test is usually normal in early IPD, but it often becomes abnormal with disease progression.

Because of dramatic heterogeneity in the expression of these cardinal motor features in IPD, patients are often subcategorized based upon the most prominent features of their motor exam. Well-recognized motor subtypes include tremor-predominant, akinetic-rigid, postural instability gait disorder PD (PIGD), and mixed [19]. Tremor-predominant patients are those with significant tremors that overshadow the other motor features of the disease, while akinetic-rigid patients have prominent bradykinesia and rigidity with little to no tremor. PIGD patients have prominent postural and gait abnormalities, while mixed patients have roughly equal amounts of all of the cardinal motor features. Recent research has suggested that these motor subtypes differ with regard to the frequency of comorbid nonmotor features, disease prognosis, and response to certain treatments [20–22]. For example, tremor-predominant patients generally have a good prognosis with slow disease progression while PIGD patients have a poor prognosis with rapid progression, dementia, and depression [19].

Nonmotor Symptoms

Along with the classic motor features of IPD, patients often suffer from a variety of nonmotor symptoms that can sometimes precede the onset of motor symptoms by several years [23]. When nonmotor symptoms are the presenting symptoms, diagnosis is often delayed at 1.6 years versus 1.0 year for individuals with motor presentations [2]. Recognition of a nonmotor prodrome of PD has instigated a debate about whether new diagnostic criteria for early-stage and prodromal PD should be created [24]; for now, however, a diagnosis of PD still requires the motor syndrome. The spectrum of nonmotor symptoms in IPD can include olfactory dysfunction, urinary dysfunction, constipation, depression, anxiety, apathy, cognitive decline, sleep disorders such as REM (rapid eye movement) sleep behavior disorder and restless legs syndrome, fatigue and orthostatic hypotension. While many of these nonmotor symptoms are common in the general population and are certainly not specific to IPD, their presence in conjunction with early parkinsonism can help further support an IPD diagnosis.

Patients with IPD should exhibit a robust and sustained response to levodopa therapy. Over time, as the degenerative disease progresses, doses need to be increased and complications of therapy are likely to emerge, most commonly levodopa-induced dyskinesia, motor and nonmotor fluctuations [25]. The various forms of parkinsonism (discussed later) may have an initial response to levodopa therapy; however, this response is generally transient and wanes quickly despite increases in dose. Many will have no response at all.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for IPD most commonly includes the Parkinson-plus syndromes (dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy, progressive supra-nuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration), vascular parkinsonism, drug-induced parkinsonism, dopa responsive dystonia, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and essential tremor. Each of these conditions will be discussed in further detail below.

Parkinson-Plus Syndromes

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) may initially resemble IPD as it can present with parkinsonian motor signs, but the distinguishing feature of this disease is the presence of a progressive dementia with deficits in attention and executive function that occurs before or within 1 year of the development of parkinsonian motor signs [26]. This is in contrast to the dementia that can develop in IPD, which usually occurs many years into the disease course. Patients with DLB often have well-formed, visual hallucinations with this disorder. Motor parkinsonian symptoms do not improve with dopaminergic therapy and caution should be used with these patients as psychiatric symptoms may be exacerbated by even small doses of these medications [27]. Diagnostic criteria for probable DLB require the presence of dementia plus at least 2 of the following 3 core features: fluctuating attention and concentration, recurrent well-formed visual hallucinations, and spontaneous parkinsonian motor signs. Suggestive clinical features include REM behavior disorder, severe neuroleptic sensitivity, and low dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia on SPECT or PET imaging. In the absence of 2 core features, the diagnosis of probable DLB can also be made if dementia plus at least 1 suggestive feature is present with just 1 core feature. Possible DLB can be diagnosed with the presence of dementia plus 1 core or suggestive feature. These criteria are 83% sensitive and 95% specific for the presence of neocortical Lewy bodies at autopsy [27]. Other supportive clinical features include repeated falls, syncope, transient loss of consciousness, severe autonomic dysfunction, depression, and systematized delusions or hallucinations in other sensory and perceptual modalities [27]. Definitive diagnosis requires pathological confirmation.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is more rare than the previously described Parkinson-plus syndromes. CBD typically presents with a markedly unilateral/asymmetric motor features and can mimic early IPD, but other defining features include cortical signs of progressive unilateral apraxia, limb dystonia and visual-tactile neglect (“alien limb” sign) that can lead to loss of voluntary control of the extremity. This sign has been reported in approximately half of all patients with CBD [34]. As the disease progresses, cognitive decline, dementia, dysarthria, postural instability and gait dysfunction can all occur [35]. Patients with CBD typically do not show any response to dopaminergic therapy. CBD brain MRI findings include asymmetric cortical atrophy (most commonly in the superior parietal region), bilateral basal ganglia atrophy, corpus callosum atrophy and T2 hyperintensities of the subcortical white matter and posterolateral putamen [36]. In recently published consensus criteria, Armstrong et al broadened the clinical phenotype associated with CBD to acknowledge the spectrum and overlapping phenotypes of tau-related neurodegenerative diseases [37]. The criteria for probable corticobasal syndrome require asymmetric presentation of 2 of: (a) limb rigidity or akinesia, (b) limb dystonia, (c) limb myoclonus plus 2 of: (d) orobuccal or limb apraxia, (e) cortical sensory deficit, (f) alien limb phenomena (more than simple levitation). Possible corticobasal syndrome may be symmetric and requires 1 of: (a) limb rigidity or akinesia, (b) limb dystonia, (c) limb myoclonus plus 1 of: (d) orobuccal or limb apraxia, (e) cortical sensory deficit, (f) alien limb phenomena (more than simple levitation). Unfortunately, these new criteria have not improved the specificity of diagnosis compared to previous criteria as shown by a recent longitudinal clinical and neuropathological study that found that all of their patients with a cortiocobasal syndrome but without corticobasal pathology had all met the new diagnostic criteria for possible or probable CBD [38]. The reader should be aware that Armstrong et al acknowledged that memory dysfunction is common in CBD, although this was not incorporated into the diagnostic criteria.

Other Causes of Parkinsonism

Vascular parkinsonism results from the accumulation of multiple infarcts in the basal ganglia and/or subcortical white matter [39]. It may account for up to 12% of all cases of parkinsonism [40]. There are not any specific clinical diagnostic criteria for vascular parkinsonism; however, the clinical presentation is somewhat distinctive. Vascular parkinsonism initially presents with gait problems, and the upper extremities are less affected than the lower extremities. Vascular parkinsonism has been referred to as “lower body parkinsonism” due to this distribution of symptoms. Patients often present with a characteristic shuffling gait, but may also exhibit significant freezing of gait, even early in the course of the disease (in contrast to IPD). Tremor is reported less consistently and other pyramidal tract signs, urinary symptoms, dementia and pseudobulbar affect resulting from various ischemic lesions often co-exist [41]. Patients tend to have a history of cerebrovascular risk factors. Response to dopaminergic therapy is present in one-third to one-half of patients and is typically short-lived [42]. Brain MRI findings in vascular parkinsonism include diffuse subcortical white or gray matter lesions, particularly involving the globus pallidus, thalamus, substantia nigra and frontal lobes. One study reported a “cutoff” point to help differentiate between vascular parkinsonism and the normal vascular changes associated with aging at 0.6% lesioned volume of brain tissue [43]. It is important to remember that microvascular lesions are commonly seen on MRI scans of older patients and therefore the presence of these lesions on imaging does not necessarily convey a diagnosis of vascular parkinsonism.

Evaluation of any parkinsonian patient should involve careful scrutiny of the medication list (current and past) to exclude the possibility of drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP). DIP is typically, though not always, symmetric in onset. Drugs causing DIP include all of the typical and atypical antipsychotics, dopamine depleters such as reserpine and tetrabenazine, gastrointestinal drugs with dopamine receptor blocking activity such as antiemetics and metoclopramide, calcium channel blockers, valproic acid, selective serotonin reuptake inhibiters and lithium [44]. Traditionally this syndrome was thought to be reversible with discontinuation of the offending drug; however, resolution can require many months and at least 10% of patients with DIP develop persistent and progressive parkinsonism despite discontinuation of the drug [45].

Dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD) most typically presents in childhood with initial onset of lower limb dystonia with parkinsonism developing over time. Symptoms respond robustly to low doses of levodopa, hence the name DRD. Occasionally, however, DRD can present in adulthood. In adult-onset cases of DRD, parkinsonism usually develops before dystonia. Because it presents with parkinsonism and is levodopa responsive, adult-onset DRD can easily be confused with young-onset IPD [46]. Clues to the presence of DRD include diurnal fluctuation, stability of symptoms over time, and a normal DaTscan (discussed later) [46].

Other rare causes of parkinsonism include exposure to toxins (MPTP, manganese, carbon monoxide, methanol), metabolic disorders (hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, acquired hepatocerebral degeneration), early-onset and genetic disorders (Wilson’s disease, juvenile Huntington’s disease, spinocerebellar ataxia types 2 and 3, and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation), infectious diseases, trauma, space-occupying brain lesions, autoimmune diseases (Sjogren’s syndrome) and paraneoplastic disorders [47–51]. Further discussion of these more rare causes parkinsonism is beyond the scope of this review; however, clinicians should always carefully consider the past medical, family, and social history, along with the review of systems, as these aspects of the patient history may point to one of these causes of parkinsonism.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) refers to chronic communicating hydrocephalus with adult onset. The classic clinical triad of NPH includes cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, and gait disturbance in the absence of signs of increased intracranial pressure such as papilledema. NPH can present with motor signs similar to those found in vascular parkinsonism, possibly due to the close proximity of basal ganglia structures to the ventricular system [52]. The gait of NPH typically shows a decrease in step height and foot clearance as well as a decrease in walking speed. This is often referred to as a “magnetic gait.” In contrast to Parkinson’s disease patients, the gait disturbance in NPH does not improve with visual cues or dopaminergic therapy [53]. Dementia also occurs early on in the course of NPH and is mostly characterized by apathy, forgetfulness, and impaired recall. Urinary incontinence and urgency is a later finding of the disease in contrast to IPD in which urinary dysfunction is often an early nonmotor symptom. MRI and CT scans of the brain reveal enlarged ventricles (out of proportion to surrounding cerebral atrophy if present) and should be followed by a diagnostic high volume lumbar puncture. Clinical improvement following lumbar puncture is supportive of the diagnosis of NPH and helps to identify patients who may benefit from ventriculoperitoneal shunting [54].

Essential tremor (ET) is characterized by postural and action tremors, rather than resting tremors, though some ET patients can have co-existing resting tremors. Though it is usually bilateral, it is often asymmetric, adding to the potential for diagnostic confusion with IPD. It typically has a higher frequency than the tremor of IPD. The absence of rigidity, bradykinesia, postural and gait disturbances and no response to dopaminergic therapy help distinguish it further from IPD [55]. There is phenotypic overlap between these two conditions and some patients with IPD have more postural tremor than rest tremor (or even postural tremor with no rest tremor), while some with long-standing essential tremor may go on to develop parkinsonism [56].

The Role of DaTscan in Diagnosing Early Parkinsonism

Final Thoughts

Despite the challenges involved, accurate and early diagnosis of IPD is essential for optimal patient education, counseling, and treatment. Careful attention to the initial presentation and examination may be all that is required for diagnosis in typical cases. In atypical cases, brain MRI to evaluate for other diseases or DaTscan may be helpful adjunctive tests. As research advances over the coming years, it is likely that additional imaging or fluid biomarkers will become available to assist us with the diagnosis of IPD (and related disorders) in the early stages. Until then, clinicians must remain highly vigilant in their efforts to make these often challenging clinical diagnoses.

Corresponding author: Leslie J. Cloud, MD, MSc, 6605 West Broad St., Ste. C, Richmond, VA 23230, lcloud@vcu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.