Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome as a Complication of Scoliosis Surgery

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is a rare and potentially life-threatening complication of scoliosis surgery. The anatomical relationship of the duodenum and the superior mesenteric artery, the correction of angular deformity of the spine, and the normal adolescent growth spurt all contribute to the condition. We report the case of a 14-year-old boy who had a history of idiopathic scoliosis and presented with bilious vomiting that had persisted for 7 days after posterior T9–L4 fusion with instrumentation. After an unremarkable immediate postoperative course, on postoperative day 19 the patient presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Unrelenting brown vomitus, abdominal pain, and a 20-lb weight loss were noted. A series of upper gastrointestinal radiographs confirmed a diagnosis of SMA syndrome. A nasojejunal tube was placed, and nutritional rehabilitation was optimized. We highlight this case for its rarity and emphasize the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion when evaluating a child who has had spinal deformity correction and presents with postoperative gastrointestinal complaints. Early recognition of the nonspecific symptoms of abdominal pain, abdominal distension, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, and anorexia plays a key role in post-scoliosis surgery and is crucial in preventing the severe morbidity and mortality associated with SMA syndrome.

Take-Home Points

- Adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome following pediatric spine surgery.

- Must recognize nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, and anorexia postoperatively.

- Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, or cardiovascular collapse and death.

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome resulting from surgical treatment of scoliosis has been recognized in the medical literature since 1752.1 Throughout the literature, SMA syndrome variably has been referred to as cast syndrome, Wilkie syndrome, arteriomesenteric duodenal obstruction, and chronic duodenal ileus.2 We now recognize numerous etiologies of SMA syndrome, as several sources can externally compress the duodenum. Classic acute symptoms of bowel obstruction include bilious vomiting, nausea, and epigastric pain. Chronic manifestations of SMA syndrome may include weight loss and decreased appetite. Our literature review revealed that adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome after pediatric spine surgery.

We report the case of a 14-year-old boy who developed SMA syndrome after undergoing scoliosis surgery. The patient and his mother provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy with a history of idiopathic scoliosis presented to Cohen Children’s Hospital (Long Island Jewish Medical Center) with bilious vomiting that had persisted for 7 days after posterior T9–L4 fusion with instrumentation.

Discussion

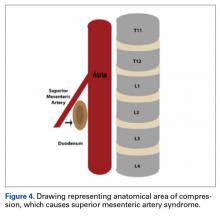

SMA syndrome is attributed to the anatomical orientation of the third part of the duodenum, which passes between the aorta and the SMA (Figure 4).

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to this condition. Faster adolescent bone growth relative to visceral growth is accompanied by a decrease in SMA angle.3 Occasionally, body casts are used after surgery to immobilize the vertebrae and augment healing. Cast syndrome occurs when pressure from a body cast causes a bowel obstruction secondary to spinal hyperextension and amplified spinal lordosis.2 This finding, dating to the 19th century, was reported by Willet4 when a patient died 48 hours after application of a body cast. In 1950, the term cast syndrome was coined after a motorcyclist’s injuries were treated with a hip spica cast and the patient died of cardiovascular collapse secondary to persistent vomiting.5

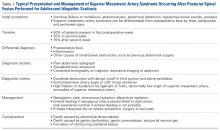

Table 1 summarizes various evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment algorithms designed to optimize nutrition and weight in patients developing signs and symptoms of SMA syndrome after posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

The third unique feature in this case is electrocardiogram findings. Although some cases briefly discussed electrolyte abnormalities, none presented evidence that these abnormalities caused cardiac changes.6,16,18 The overall clinical significance of the QT prolongation in our patient’s case is unknown, as this finding was improved with correction of the electrolyte abnormalities and appropriate fluid replenishment.

Early recognition of nonspecific symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, tenderness, distension, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, anorexia) plays a key role in preventing severe morbidity and mortality from SMA syndrome after scoliosis surgery. Although many patients present in the semiclassic obstructed pattern, notable reasons for diagnostic delay include normal appetite and bowel sounds.3 For example, SMA syndrome may be misdiagnosed as stomach flu because of unfamiliarity with disease diagnosis and management.20 Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, and cardiovascular collapse and death.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):E124-E130. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.