Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy apical variant

He had had an isolated syncopal episode while intensely training a year ago, but his medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, he appeared fit. His vital signs were normal. The apical pulse was sustained on palpation and was not displaced. Auscultation revealed an S4 heart sound.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY: THE APICAL VARIANT

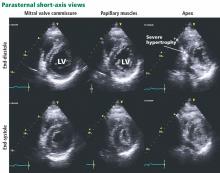

,In typical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the left ventricle, especially the interventricular septum, is thickened, but the left ventricular chamber size is normal or small. In severe cases, the left ventricular outflow tract can become very narrowed, resulting in accelerated blood flow, which may further increase in the presence of hypovolemia, peripheral vasodilation, and increased cardiac contractility. The Venturi effect thus created may entrain a typically malformed anterior mitral valve leaflet toward the aortic valve (systolic anterior motion), causing mitral insufficiency and exacerbating obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. Systolic anterior motion may play an important role in exercise-induced syncope and sudden death in young people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.4

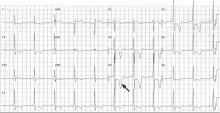

In the apical variant, hypertrophy is confined to the left ventricular apex.1–3 There is no dynamic outflow tract obstruction. Still, unexplained syncope has been reported, and recent data challenge the conventional wisdom that the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has a benign prognosis.2 In patients without a history of recurrent syncope, chest pain, or heart failure, perioperative risk is probably not significantly increased. The differential diagnosis includes myocardial ischemia or infarction, electrolyte disturbances, effects of drugs (eg, digoxin), and subarachnoid hemorrhage.1–3,5 Plain or contrast-enhanced echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or both, can help confirm the diagnosis. Long-term management should be guided by the patient’s symptoms.